|

Chapter VIII

It was early February in 1920 and O’Neill was eager to

hear how Beyond the Horizon would fare as it opened at the Morosco

Theatre in New York. He had been informed he was to be awarded the

Pulitzer Prize in drama for this play. His first reaction was negative

and he did not want to go to the ceremony. O'Neill had never felt

comfortable with the fanfare connected to receiving honors or awards.

Finally, realizing it would offer him much prestige in the theater

world, he made plans to attend. He sent an inscribed copy of the play to

Margery.

In the city, attending rehearsals, Gene was able to

spend a good amount of time with his parents. It was March and Agnes was

alone with Shane in Provincetown. She wrote to the family in Jersey

saying she was lonely and explained that Gene had been in the City since

early January, agonizing over rehearsals of a new play. His father had

suffered a stroke, but was now well enough to attend the opening, and

feeling extremely proud of Gene’s receiving the Pulitzer. Aggie wanted

to be down there too, to celebrate with Gene.

Agnes also mentioned she had found a woman, Mrs. Fifine

Clark, to help with Shane. But Mrs. Clark could not come for awhile, and

this concerned Aggie because she had been in bed for a week or so, very

exhausted. She said the doctor was keeping an eye on her and not to

worry. She described five-month-old Shane as being very active and dear,

but very demanding. Shane had now become Shane the Lord!

|

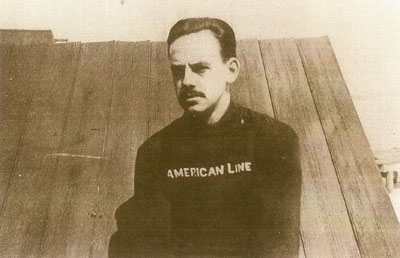

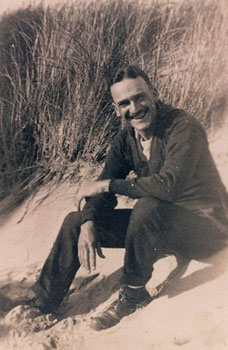

| Gene in a

favorite sweater, circa 1919-1920. |

|

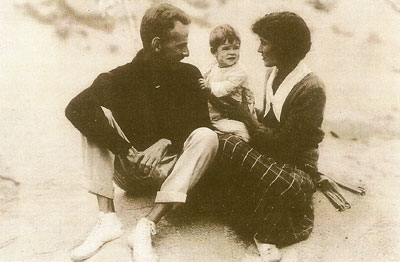

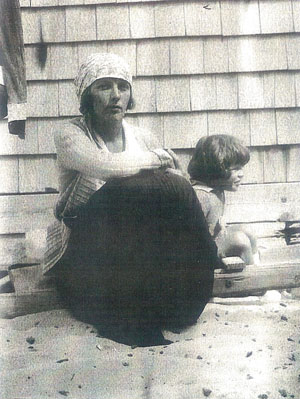

| Agnes and

Gene with "Shane the Loud," circa 1919-1920. |

Aggie's letter closed with a message to please tell

Cookie her mother loves her, and maybe she can come up to the Cape to

visit in the summer at Peaked Hill Bars.

Another letter to Ted and Mother Cecil came from

Margery. At age twenty, she had been married in January to a man named

Carlton Stevens.

Dear Teddy and Ma,

We’re living in a small house on a lonely lake in

Waterbury. We took the motorcycle out on the ice. It’s been frozen

over for a time. We do some racing and “crack- the-whip” on the ice.

I’ll send a picture… but it may be later in the spring. Hope to get

down to see you one of these days.

Love to all, Budgie

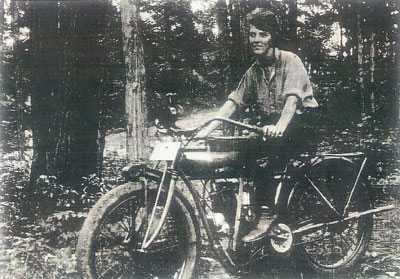

Margery won a motorcycle at a show in New York. The

Indian bike lasted a long while. The marriage lasted less than a year.

|

| Margery

Boulton on Indian motorcycle she won in New York, 1920. |

It is interesting to note that in 1920, when casting was

being done for The Emperor Jones, Charlie Chaplin, who had become a

famous actor, showed up at the theater. Always an admirer of the

Provincetown Players, he went to a rehearsal of the play and told Jig

Cook (George Cram Cook) that he would like to play a part of one of the

ghost convicts, under another name. After much discussion by the

Players, it was decided if audiences ever found out it was Chaplin, they

would come to the play looking for him and not to see the play. Chaplin

bowed out reluctantly. Who could have known that years later Charlie

would marry O'Neill's daughter Oona?

O'Neill's Chris Christopherson opened in Atlantic City on the 8th of

March. Just before leaving to go back to the Cape, Gene learned his

father had been diagnosed with stomach cancer after the stroke. The

whole idea frightened Gene. Writing of death was one thing, but actually

dealing with death was another. In the city, Gene had word from Agnes

that she was sick in bed. Very concerned, he left immediately for

Provincetown to be with her and Shane.

Agnes was up and about, feeling much better, when Gene arrived. Summer

was approaching and she was packing boxes once again for the return to

Peaked Hill Bars. It was a quiet spring at Peaked Hill, with contented

days on the beach and in the sun. Margery joined the family for a visit.

|

Another summer in

Provincetown, circa 1921-1922. |

|

|

| Gene Jr.,

Agnes and Shane in skull |

Agnes and

Shane |

|

|

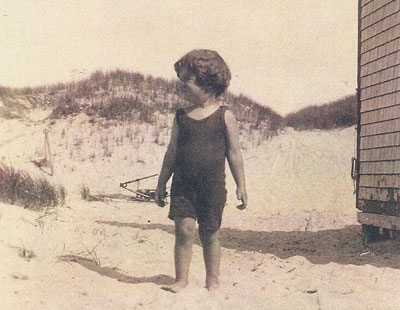

Shane |

Looking through old photographs, I found a small photo of my mother,

Margery, on the beach with Gene and Saxe Commins, and another one alone

with Saxe. Saxe was a dentist who had given up dentistry to go into

publishing. He later became a life-long friend of O’Neill. On the back

of the photo Margery had written “Broke engagement to Saxe.” This was

something she had never mentioned. No one seems to know more about it

than that. I do know Margery befriended his sister, Stella Ballentine,

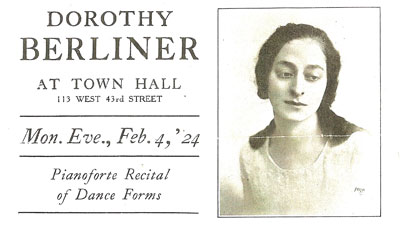

also a friend of Agnes in Provincetown. Later she talked about Dorothy

Berliner, Saxe’s wife and an excellent musician. She had saved a program

from one of Berliner’s concerts.

|

| Agnes and

Saxe Commins, circa 1920-1921. |

|

| Margery,

Gene and Saxe with unidentified dog, circa 1920-1921. |

|

| Dorothy

Berliner, Town Hall concert, 1924. |

Young sister Cecil was visiting at the Cape with Gene and Aggie when

Gene presented her with a copy of Beyond the Horizon. It was then she

met Eddie Fisk, an artist and friend of the O'Neills. He later became

Cecil's husband.

|

|

| Cecil II,

little Shane and nurse, Mrs. Fifine Clark, 1921. |

Eddie Fisk,

who later became Cecil's husband, 1921. |

|

Budgie and

Shane in Provincetown. |

At the end of July news came that James O’Neill was dying. Gene left

immediately to be with him, and with his mother and Jamie. After days of

pain and distress, James went into a coma and finally on August 10th he

died with his family around him. Agnes took little Shane with her when

she went down to be with Gene's family.

The funeral in New London was a grand tribute to the old actor. The

large number of mourners included theater fans, people from Irish

organizations, and many from his own community. It was an impressive

service. Gene and Agnes were glad they had taken Shane down to see him

earlier in the summer, as James had been completely delighted with this

handsome child named for a great O’Neill in Ireland.

With my mother Margery’s treasures was an old clipping from

The Sunday

News (a New York paper), December 30, 1956. It was an article written by

John Chapman, a drama reporter and later a critic for The Daily News,

and a colleague of James O’Neill. He stated that “Long Days Journey Into

Night was an unfair picture of Eugene’s father.” The article described

the many parts the senior O’Neill played, aside from the six years in

The Count of Monte Cristo. He wrote: “James O’Neill loved his family but

he was a disappointed father. He was saddened by his wife’s sickness and

his son’s actions. The old New Londoners will tell you James O’Neill was

a good provider, but a sad man and a bit embittered. He played New

London in 1912 in The Man in the Box and O’Neill was not the drunken

father depicted by the elder Tyrone.” He went on to suggest Eugene must

have realized that he had taken many liberties with the truth when he

wanted the play to be held for twenty-five years after his death,

“Perhaps he was ashamed he had made an inference the play was a picture

of the actual family,” Chapman concluded.

To ease their suffering after their father’s funeral service, Gene and

his brother Jamie went on a drinking binge that lasted several weeks.

Agnes went to New Jersey with Shane to visit her family and Cookie.

Gradually they all found their way back up to Peaked Hill and some days

of peace on the shore, fitting for the last of the summer.

During the winter spent in Monroe House on Bradford Street in

Provincetown, Madame Fifine Clark had come to join the family. Shane

adored her, and she worshiped the little boy with a head of thick brown

hair and a winsome smile. Gene began work on The Hairy Ape.

Anna

Christie opened on November 2nd at the Vanderbilt Theatre.

Early summer in 1921 the Boultons had moved for the

season to Milton, Connecticut. A letter from Ted, written to Agnes, had arrived in the

morning mail from The Birches in Milton, Connecticut.

Dear Girl,

Your mother is a little overwhelmed with all the family members

who have descended…but she handles these surprises well.

Cecil arrived last week with Eddie Fisk. They were recently married.

I do like him… he’s an interesting young man and we enjoy talking

“shop.” He’s a fine artist in my opinion, and an enthusiastic fellow. Cis seems happy. They are staying upstairs. Bobby and Walter are

here, too. Their baby is due any time now. If it’s a boy it will be

William, and a girl will be another Margery Winifred. We do keep

names circulating in this family, don’t we?

With all these people, it’s a good thing the weather is warm

and we can use the porches. Hope you’re doing well now. Glad you

feel better. We’ll try to see you during the summer. Mother sends

hugs to all, too.

Love, Ted

Agnes wrote to her father: “Come up and visit! Get yourself away from

the over-flowing family…too much in one house. You can paint to your

heart’s content and see our darling Shane.”

Ted went up to spend part of the summer with Aggie and Gene at the Cape,

painting endlessly and loving the change. Gene presented him with a copy

of The Moon of the Caribbees. This same year there was also a family

celebration when Gene won a $25,000 Pulitzer prize for Anna Christie.

Jamie arrived for part of the summer season as well. He was quite taken

with Margery when she was visiting, and it has been told that he

announced one evening, “Marry me, Budge, and you can be my widow and

heir!” Budgie told me later that was a made-up story, but she was fond

of Jamie and felt sad about him. She sometimes felt he wanted to die.

The year 1922 brought with it sad news and good news. Gene’s mother,

Ella O’Neill, died on February 28th. It was another difficult time for

Gene, his mother being the most special member of the family, and her

death meant an empty place in his soul. He was devastated. Jamie also

suffered dreadfully and began another long bout of drinking. Ella had

done so well these last years dealing with her addiction to morphine,

even after her husband James had died. She had missed him terribly but

though Jamie wasn’t much help, she remained stable. Jamie tried, but

drink was too much a part of his life.

The good news followed on March 9th when The Hairy Ape opened at The

Playwright’s Theater. Gene felt strongly about this play, and though

glad to see it in production, he was dismayed that his audiences were

not comprehending the message he intended. They did not seem to

understand the play was expressionistic — Yank was a symbol of every

human being trying to “belong.” Gene felt that no one seemed able to see

that Yank represented each one of themselves. As well as the audience

reaction to The Hairy Ape depressing O'Neill, he also was not able to

shake the feelings he had about his mother’s death. For him it was a

time of deep distress and grieving.

Looking closely at the reaction O'Neill had about The Hairy Ape and

Yank, we may be able to understand the man more deeply and see better

into the depth of his spiritual and philosophical leanings. This

may help us all to follow, with words, the path he chose to pursue and

the effect it had on those around him and on the plays he wrote. The

impressions we may carry of this challenging and complicated figure can

raise endless questions in our minds. We cannot pretend to know his

thoughts and deeply personal musings, but we do have available his

projected thoughts, philosophical ideas and some of his spiritual

reflections from the characters in his plays and from his writings.

What is it about Eugene Gladstone O'Neill and his plays that fascinate

so many people around the world...including O'Neill scholars? Is there a

desire to understand a side of O'Neill or his characters they see in

themselves? Can they perhaps touch the roots of the negative, the

cruelty, sorrow and pain hidden within each of us? O'Neill shows this

not only in his own life but in his many-faceted characters.

O'Neill, it seems, liked using his characters to portray the idea of

man's intense desire to “belong,” as Yank in The Hairy Ape. These

characters often find themselves cast between the physical world and the

spiritual world, not fitting in completely with either. As a result they

are constantly searching for a meaning to life.

Gene O'Neill was a man of mystery, complex in his moodiness, with a mind

so ready to grasp any understanding of the human soul, one might wonder

if he had the ability to see beyond the physical and into the deep

recesses of our minds...recesses hidden even to ourselves. When his

players cry out in agony and grief, we hear our own cries for help, and

we hear too, O'Neill's desperation. He often stated it was not “man in

relation to man, but instead man in relation to God” being the important

element in our eternal search for the understanding of why we exist.

O'Neill seemed to play with thoughts and ideas as though by chance he

might win the “game of life” and on the way come upon an eternal truth.

The frenzied outpouring of O'Neill's plays describing dark human tragedy

makes us wonder if it became one way in which he could keep a sense of

sanity in the face of some unbearable discovery in his own search for

the meaning to life.

In his book on O'Neill, The Curse of the Misbegotten, Croswell Bowen

believes the curse lies in the idea there was an absence of love, and

the feeling of isolation with a failure of give and take in the O'Neill

family. This is certainly true, but was there something more? Here is a

man who could communicate to the world through his writing of drama and

poetry, but seemed totally unable to communicate closely with his

family.

One can contemplate the emotional and psychological leanings of O'Neill

but to understand the total man, I believe one must also include the

spiritual side of his life. He seemed to be in touch with the so-called

“soul of man” as he searched for his own. We know he left the Catholic

Church and went through several spiritual phases, some denying a God,

but during one period talking of his writings as “man's relationship to

God.” He described his dark side as dealing with the Furies, but there

often seemed to be a question. When he knew he was dying he called two

priests to come to his bedside. Had O'Neill found this understanding he

so desperately searched for, would the world have missed the brilliant

theater which the genius inside him was able to produce?

In The Hairy Ape O'Neill creates a spiritual connection between Yank and

all humanity. He describes Yank as the symbol of “being yourself and

myself...every human being.” But as O'Neill watched the performance he

felt that few, if any, of the audience understood this. No one seemed to

comprehend the underlying meaning of the play... “I am Yank! Yank is my

own self!” Yank is recognizing he is not only himself but every other

being.

Louis Sheaffer in his biography of O'Neill suggests he was “launched on

a lifelong quest for something to believe in.” O'Neill joined us all in

this struggle to find the thread of connection that would make us a part

of the “fabric of life.” The fact that he was able to create this

connection with the character of Yank can touch us deeply and yet it was

sad that he couldn't seem to find it in himself. The idea certainly

expresses the constant yearning we so often have, to know who we are and

how we “belong.”

Another example of the mind-workings of O'Neill is in Long Day's Journey

Into Night, and it reinforces the idea of connection that he portrayed

with Yank in The Hairy Ape. Not an enthusiast of Freud, O'Neill did feel

an enthusiasm for Carl Jung, and especially liked Jung's theory of the

“collective unconscious,” or the archetypal mode of thought that is

derived from the experience of the race and is present in the

unconscious of the individual.

Edmund, who represents O'Neill in the autobiographical

Long Day's

Journey, is talking to his father one evening, and “with alcoholic

talkativeness” having had too much to drink, talks of his connection

with the sea. He describes how he lay in the bowsprit with the foaming

waters beneath him, and the masts with white sails in the moonlight

towering above him. Feeling the singing rhythm of it, he feels as though

he had lost himself, lost his life, and was suddenly free as he became

connected with all around him. Edmund is expressing beauty, the

pulsating rhythm and a sense of belonging to something greater than his

very life; to Life itself or to his God.

Edmund, talking about a third ocean voyage, again describes a moment of

ecstatic freedom, feeling the joy of belonging, being a part of the sea,

the peace or “the last harbor.” He talks of other times, always

connected to the sea as he swims, or being on the beaches, and seeing

“the secret”...being the secret. He seems to have had truly spiritual

experiences and then as he describes it, he goes back “into the fog”

again.

These touching passages on the connection of our being with all, the

same feelings he wanted us to see in Yank, are perhaps more clear if we

have at some time experienced in ourselves that joining with all life

and beings around us. It is obvious that O'Neill himself felt the way

Edmund describes, and therefore can portray a character in his play

having the same experience.

There is a speech that follows Edmund's beautiful description of

connection, and is often quoted, about “being born a man but perhaps

being more successful had he been born a seagull or a fish, and being

the stranger who never feels at home, never belonging, and always being

one of the fog people.” This seems to become a less exciting quote than

the full description in the play when Edmund has a true sense of

“belonging,” but it does describe a real experience of connection, even

though ending up “in a fog.”

Chapter IX

Chapter IX |