|

Chapter XXI

“The past is the present, isn’t it? It’s the future,

too.”

Mary Tyrone from Long Days Journey, Act II, Scene 2

A few final reflections I feel important to add to this

story as we pass through and come to an understanding of the impact felt

by others in the family. First, about Gene O’Neill...he will live with

us one way or another until we are gone. Then another generation will

take on some of our memories, and so on, until the memories have faded.

We have felt the fingers of his fame as they reached out to touch all in

the O’Neill and Boulton families. The effect of O’Neill on various

members of both families was profound.

In examining the relationship between Agnes and Gene

O'Neill, it is interesting to note the difference from the relationship

with her immediate family, the Boultons. The family called her Aggie,

and she was the queen. She ruled firmly and with an air of superiority.

While her mother was at times dependent on her for some financial care,

the family often felt she wielded an additional control over them. It

seemed most decisions were made with Aggie in mind. Agnes often set

herself apart from her siblings and appeared to make a life of her own.

Strange how in her relationship with Eugene O’Neill, she took the

opposite stance and became the dependent caretaker in many ways.

The impact Eugene O’Neill had on Agnes Boulton's life

was complicated. Again, my point of view has been formed through what I

learned from my mother, Budgie, from living next door to Agnes when I

was a child, and from spending time with Agnes many years later when we

cared for her mother, my grandmother Cecil, who had suffered a stroke.

Agnes, an accomplished writer herself, stepped into a

relationship with O’Neill, who was on the verge of achieving great fame.

Competition had to be quite strong. Underlying the attachment to Gene,

Aggie seemed to have a need to care for and protect him. She made

certain everything was run according to his needs and wishes. However,

she must have felt an unspoken resentment that her own needs as a writer

were not always being met. I also had a sense from stories Budgie had

told that Aggie was afraid if things did not go just as Gene wished, he

would leave her. A caring person, she must have felt terrible guilt and

pain in regard to leaving little Barbara with her mother because Gene

did not want Barbara with them.

I believe Agnes must have felt betrayed when Gene

abandoned her. To please him, she had devoted herself only to him as she

turned her children over to others for their major care — Barbara to Nanna and Shane to Mrs. Clark. Oona was born at the end of the

marriage. Agnes had sacrificed much of her own blossoming career as a

writer to nurture Gene's career. She must have felt much unexpressed

anger. It certainly came up in some of the family letters. This kind of

“sacrifice” is never without guilt in the other person. I think of

Hickey in The Iceman Cometh, who on killing his wife says, “I

couldn’t forgive her for forgiving me. I caught myself hating her for

making me hate myself so much.” Perhaps O’Neill was relating to Agnes as

he described the force in the so-called love that Hickey’s wife bore her

wayward husband, a love that mingles a false and martyred understanding

and forgiveness, and becomes not love at all.

Interesting to note is that in an old news clipping

about Agnes’ death, Gene is quoted as saying to her that she failed to

live up to what he wanted in a woman, which was the ability to be

“mistress, wife, mother and valet.” He later seemed to find some of this

in Carlotta, who doted on him in many ways, and with no children to

interfere.

There was tremendous turmoil in the ten-year marriage

between Agnes and Gene O’Neill, and this stormy relationship may have

had something to do with the strength of the particular plays which were

written during that time. He wrote Beyond the Horizon in 1920,

Anna Christie in 1921 and, toward the end of the marriage,

Strange Interlude in 1928. All three won Pulitzer prizes.

Agnes herself became a published author with two

successful books, The Road Is Before Us and Part of a Long

Story, as well as a film play and many magazine stories.

As we know from his history, Shane Rudraighe O'Neill seemed dramatically

impaired psychologically by both his mother and father. Abandonment and

serious rejection haunted him for most of his childhood and throughout

his life.

Shane was away at school so much of the time that I knew

him, I felt on the periphery of his life. I was eight years younger and

saw him at The Old House in the summers. As a baby, he had been an

important little character called “Shane the Lord” by the family. By age

eight, his father had gone and Agnes was busy with a new life and away

from home much of the time. My impression of Shane as I look back is

of a child who led a lonely and emotionally painful life in the shadow

of his often absent parents. He spent most of his early years in

boarding schools, coming home in the summers for two or three months.

His shy smile is what I remember best. That smile, I decided later, was

a brave cover for the lost soul — the little abandoned soul — he carried

inside.

Budgie told a whimsical story of Shane as a small boy,

selling his autographs to strangers on the beach: “I’m Eugene O’Neill’s

son. If you give me a quarter, I’ll write my name for you.” Perhaps this

is a revealing tale, describing how many members of the family felt in

relation to the famous O'Neill!

|

|

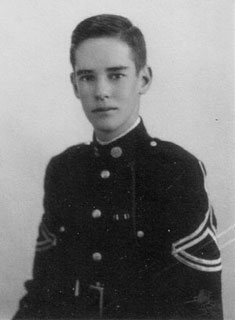

| Shane at

Military School, 1935. |

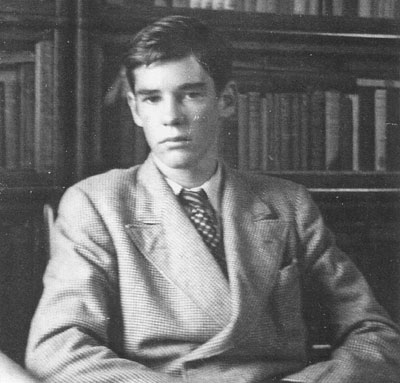

Shane and

Cathy with their children, Ted, Maura, Kathleen and Sheila,

1959. |

Sensitive and fragile, Shane seemed unable to believe he

would ever measure up to the great man he believed his father to be. He

attempted over and over to imitate the life young Gene had lived, going

to sea, writing poetry and hanging out in bars, drinking. He seemed to

have a need to convince himself he was an equal to his father. Even as

he did all this, it appeared he felt defeated by life before his own

life had hardly begun.

|

|

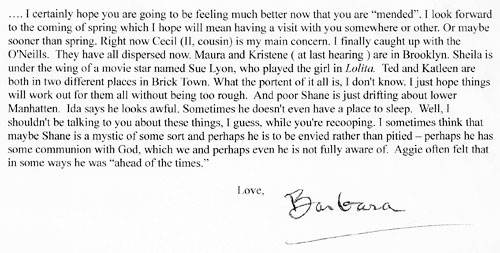

| Shane and

part of letter from Barbara Davis to Budgie. |

There was a close relationship with a young woman,

Margaret Stark (sometimes called Muggsie), who was a student with

Shane at The Art Institute in New York City. I remember once when Shane

brought her down to meet the family in West Point Pleasant. Margaret, a

lovely young woman, seemed as soft and gentle as Shane. Both interesting

and talented, they were close friends.

Shane turned into a fine artist in his late teens and

early twenties. My brother and I remember his drawings and sculpture. A

passionate fascination with horses showed in his work. Looking back, I

wondered if horses symbolized a need to control the strong figures in

his life.

Joining the Merchant Marines in 1942 when World War II

was in progress, Shane sailed between Africa and England on a supply

ship. It was not all easy, resulting in his last voyage in the fall of

1943, when he was discharged and went into a hospital to be treated for

severe shock. He had been one of two survivors on a ship that was blown

up. He had witnessed the bombings, and at one point held a dead marine

in his arms in the water for two hours. This was after seeing the men

jumping from sinking ships into flaming waters. These horrors would not

leave him.

For many years Shane's bravery in the Merchant Marines

was never recognized because the Merchant Marines was not considered a

part of the United States Armed Forces. Shane was not considered a

veteran. Even though President Clinton proclaimed in 1994, “The Merchant

Marines' sacrifices were crucial to victory,” the government did not

recognize them. It took a lifetime of waiting, but several years ago the

government finally accepted the fact the Merchant Marines were an

important part of the military, and Shane's family received a packet of

his papers and records. At last he is being considered an honored

veteran.

After his return from the service and Shane was home

once more, he began to ease his pain with drink, and twice tried to take

his life. Margaret rescued him both times and suggested therapy. Therapy

didn't help Shane. Today he would be treated for posttraumatic stress

disorder. In those days family problems were blamed, and no one seemed

able to help him. Shane was undoubtedly dealing with a combination of

the horrors of war and his feelings of worthlessness from abandonment by

both parents.

Sometime after he walked away from his relationship with

Margaret Stark, Shane met and later married Catherine Mary Givens in

July of 1944. They had four children and moved from Florida to Bermuda

and back to West Point Pleasant, New Jersey. Cathy managed to keep some

stability in the family despite Shane's mood swings and drug problems.

They spent many years living in The Old House while Agnes was in

California. Then for a time they moved into a little cottage Cathy

bought from an inheritance her family left to her. Shane's death in June

of 1977 was a dreadful shock to all the family, and ended the life of a

very sad and sensitive man.

Our lives touched only a little after the West Point

Pleasant days, but I knew Cathy and admired her spirit. She was an

amazing woman to have kept her family together during such stressful

times. Shane’s four children have grown up with a sensitivity inherited

from their father and a stability encouraged by their mother, both

helping them to step out from under the dark shadow of tragedy they

might have taken on. Each one seems to have a strength of his or her own

that allows them to be who they are without having to carry the negative

side of O’Neill’s fame. They can enjoy it but do not seem to be

obstructed by it.

|

|

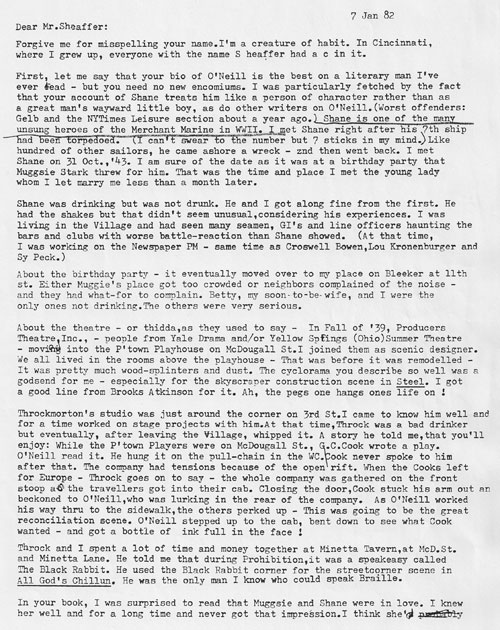

| Letter from Bernstein to Lou Sheaffer

about Shane. |

Though I did not know him, I’ve included Gene O’Neill,

Jr. because I’ve read so much about the disturbing life he lived. He

too was seriously affected by his father’s fame and fortune, and also

by O'Neill's absence for many of his early years. This information has

been in most books on O'Neill. I only repeat it for those unfamiliar

with the whole story.

After meeting his father at age thirteen, young Gene

began to come into his own. He studied hard in school, wrote many

letters to his father, to which his father responded. Gene Jr. spent

time in the summers with the “new” family. Young Barbara developed quite

a crush on this handsome boy, as they played on the beach and swam

together. O'Neill was delighted that his first child showed a great

interest in literature and poetry, and was thrilled when Gene Jr. earned

a doctorate in Greek from Yale, a degree which led to his becoming an

assistant professor at the University. All this was held up to Shane,

who was desperately finding his way along other paths. O’Neill

disinherited both Shane and Oona as time went by, which seemed to draw

him closer to his eldest son. There must have been much guilt carried by

both with this change in events.

Gene Jr. liked his visits with Shane and Oona and talked

with Shane about “our father.” He was taller and huskier than Shane,

handsome with a Vandyke beard and was very popular for a time. He was

unable to get into the service during the war because of allergies and a

permanent injury from a bicycle accident. At one time he worked as an

announcer on Hartford radio WTIC in Connecticut. He was seemingly one of

the family touched by the so-called “curse of the misbegotten,” and

after three divorces and difficult times with losing teaching jobs, he

took his own life. He had quoted Shakespeare to friends the evening

before his death: “There’s a divinity that shapes our ends. Rough hew

them how we will.”

Sadly we can see still another child painfully affected by the O'Neill

syndrome. Barbara Burton Davis was an especially pretty child and grew

into a beautiful woman, carrying a gentleness about her, which showed

when she talked about small birds and animals. Many a stray had she

taken in and cared for over the years. I remember her adopting a wasp

who made himself at home on her window sill. She fed him sugar and water

from a spoon. Psychologically speaking, this extreme concern for

helpless small animals and creatures often reflects a childhood of

abandonment and hurt. It demonstrates the kind of caring a child wishes

for so desperately. Barbara's anger, which came out when she talked

about newspaper reporters prying into her life, was perhaps the same

anger she may have felt during her days in boarding school when she was

questioned about her relationship to the O'Neills by curious teachers

and schoolmates.

On the other hand, a sophisticated, rich speaking voice

expressed the wisdom Barbara held about life, and a delightful, lilting

laughter brought out the humor she was ready to exhibit at any time.

Both these show in her poetry.

I feel that in her early adult years, Barbara dealt with

the lack of a stable family life and the O’Neill influence in a very

constructive way. Living in an apartment on MacDougal St. in Greenwich

Village for many years, she became interested in the theater. Barbara

sang and took a bit part in the chorus of Our Town when it played

on Broadway. Another time she was doing some secretarial work for

Leopold Stokowski when he was conducting in New York, and kept up a

correspondence with him for some time. She was making an interesting

life for herself.

Barbara later worked in her own studio on Broadway as a

film editor. I remember going to New York to stay with her for a short

time. I was nineteen or twenty and she took me to the studio where she

was editing Abie's Irish Rose. Pieces of film lay about on the

floor. I was most impressed as I tried to imagine how she knew which

parts to cut and which parts not to cut. Now I chuckle at the idea of

work such as this, the power to cut up and remove parts of the scenes in

the lives of the people in these stories. She certainly cut the scenes

of despair in her own life by trimming them carefully as she went

through her days.

Barbara outlived her siblings and went into her later

years with grace, managing a creative and generally satisfying life,

except for the times when she became very angry about newspaper people

trying to find her. She was convinced they were all determined to find

out about her days as a child with the O’Neills. She became more and

more uncomfortable with anyone but her immediate family knowing or

talking about the relationship. She was obsessed with believing

reporters and others were intruding on her life and it became very

agonizing for her. The family felt she had exaggerated the problem and

may have actually been running away from the pain of her childhood. It

was during this time she changed her name from Burton to Davis.

She moved away from her beloved New York City and set

herself up in a small apartment in upstate New York, where she studied

and began writing poetry. In time she became a published poet. Later on

she left each of us a lovely book of her own poetry. One poem we all

like is called “Remembering.”

Yellow stars

fallen to black earth

beneath forsythia bushes;

the yellow cheesecloth dress

she wore as a children’s

in a one-act, one-character play

for Nanna's birthday

in Merryall

where Stokowski lived.

Years later seeing him

with his great white mane

and blue shirt

and waving his arms, his pursed lips

as he conducted Mahler,

reminding her

of daffodils

blowing in the breeze

along a lake shore.

A second and third move to other towns and states helped

in keeping Barbara from thoughtless prying eyes and ears, even though it

never seemed to end. We found an unpleasant story about her and her

mother Agnes in a Connecticut paper in the 1990s, as thoughtless

reporters were still trying to publicly solve the mystery of her birth.

One of our cousins told her about it, and that was the last straw for

her. She moved far away to Pennsylvania to be near her relatives in the

Jones family.

Barbara never married, though she told us she had when

she changed her name to Davis. One day she said to me “Barbara Burton is

dead. She no longer exists!” In later years she sometimes talked, with a

twinkle in her eye, of the few men in her life. She enjoyed her

singleness. We enjoyed her stories.

The earlier letter from Barbara to the New York Times

at the time of her mother’s death gives a telling picture of how

completely and how sadly she covered over the hurt she must have felt in

her relationships with all the O’Neill family, including her mother. The

distress must have lain deeply buried as she defined and defended each

family member through her entire life.

We remember the way Barbara defended her stepfather when

Oona talked about how much she realized she hated him. In the letter

about her mother, Barbara says how well she remembers the good times

when she was with Agnes and Gene. The fact she remembers so well hints

to me that they were few but special times. I do admire her having

compensated so completely and for not turning her life into one of

depression and self-pity. She seemed always a truly remarkable woman,

living to be ninety-three years old, near Maura and Kerry Jones who

helped take care of her in those later years.

My mother Margery, or Budgie as we all liked to call her, seemed to

delight in the fact she had been related by marriage to Eugene O'Neill.

She also enjoyed the fact she had helped Gene by typing his manuscripts

for him and had lived with the family quite a bit of the time during

their ten year marriage. She loved to show us the many photos she had

taken at the old Coast Guard Station called Peaked Hill Bars, on Race

Point in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and at Spithead in Bermuda…photos of

the O’Neills and Boultons and their friends in that special world. Many

of these photos are now in the Sheaffer Collection at Connecticut

College, some are with Dr. Harley Hammerman in St. Louis, Missouri. Next

to Yale, he owns the largest known collection of O'Neill books,

artifacts, photographs and papers in the country. A few pictures remain

with me.

Budgie told many stories of her days with Gene and Agnes

over and over during her life. These stories are what we have inherited,

and they have kept the spirit of the O’Neills alive as part of our

heritage. She lived to be ninety-three years old, when in 1994 she died

peacefully at her home in Connecticut.

|

Our Budgie

Margery Boulton Colman

1900-1994. |

Budgie held a special place with Agnes’ family during

those ten years, and then went off to make her own life with two

children and her mother (Cecil), carrying with her the fascinating

memories and tales of days she never wanted to let go. Budgie gave me so

much with her wise insights into life in general. She opened my eyes to

much of the historical and political understanding I might have missed

had she not been so educated in these fields. Photography excited her

from those early years at the Cape and in Bermuda, and throughout her

life. Every autumn in her older years she would pack her camera

equipment in her little green Volvo and head for the New England coast.

She especially loved Maine with its wild waters and rocky coastline. At

the same time she was always ready with a good story if you mentioned

the O'Neill days at Cape Cod, Brook Farm or Bermuda.

Oona was without a father for all but the first three years of her life.

It seemed she looked to her older brother Shane during her early years,

and then to her husband, Charles Chaplin, to fill the need for a father

figure. Shane, very needy himself, was home only in the summers. Oona

married Charlie at age eighteen and he offered the security she had

desperately wanted as she was growing up. Charlie was there for her

until his death on December 25, 1977. Her marriage to Chaplin had given

her the safety, security and family she had so hungered for in her young

life.

Remembering Oona when we were children, I need to see

past the adoration I felt toward her, a slightly older cousin by a

little less than two years. My image of her as a child was her holding

an air of importance even as a very young person. She was clear about

being the child of Eugene O’Neill, even though he had abandoned and

rejected her and moved thousands of miles away. On the other hand, his

fame and fortune perhaps helped her in feeling important and worthwhile.

There was an aura of determination about Oona, which may

have covered any insecurity and, perhaps, the fear of losing the rest of

her family. Not only did Gene O’Neill leave her as a three year old, but

he also rejected her again as a teenager when, in 1942, she was named

“Debutante of the Year.” He felt this was beneath her, and was angry

with Agnes for having allowed Oona her “coming out” in the New York

social scene. He disapproved intensely of her marriage to Charlie, which

was a slap in the face to him. Charlie and Gene were close in age. This

time O’Neill totally disowned her and was never in touch with her again.

She was sixteen the last time she saw her father. Later on she named one

of her children Eugene.

I believe Oona’s childhood was very important in

relation to the rest of her life, and I have put down what I remember,

as best I can. Perhaps it will help to explain some of the mystery with

which Oona surrounded herself.

Charlie’s life has been described in many books and

stories. Oona’s life was a quiet secret, which she kept buried for her

lifetime. I hope the parts which I have filled in may help her family to

know her better and to understand her untold story. Two books written

about Oona left out a great part of her childhood. Living in the

Shadow and Being a Hidden Star both missed something

important. I feel she never truly “lived in the shadow” or became a

“lost star.” During her years with Charles Chaplin I felt she was

exactly where she wanted to be. She had many ghosts to deal with but she

managed to put them all aside and not let them interfere over the years

with Charlie and their eight children. It seemed she didn’t talk with

her family about the relatives she left behind in the States,

but to her great credit she had left a troubled childhood and went on

with a new life. Charlie, being a devoted husband, gave Oona the

happiness and security she so much needed.

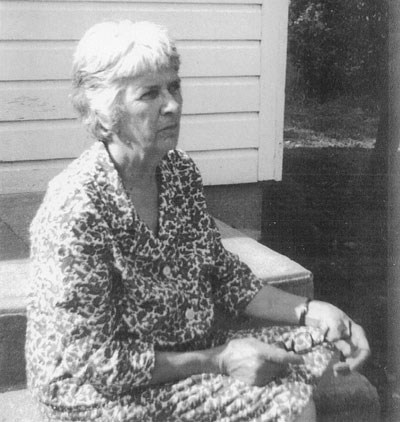

|

| Charles and

Oona Chaplin. |

|

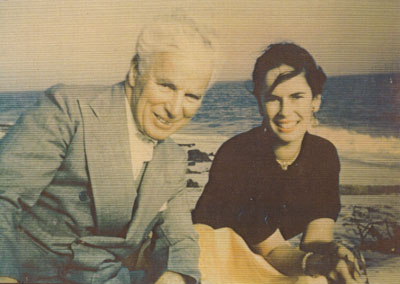

| Chaplin

study with Eakins painting and photos of Gene and Agnes,

circa 1960s. |

Oona protected herself by not talking of the past.

There was a control and an image of self-assurance, which covered the

fears of abandonment and perhaps of not being totally sure of herself.

“Be the leader, the mother, the teacher and you cannot be questioned. No

one can get to you or touch you. You are the authority.” She laughed

when she told me she played in the stock market. This carries a power

with it. She knew her mind from the early days when she refused to go to

college, and took that strength into her marriage and family life.

It's a shame Gene O’Neill never really knew his

daughter, and never established a close relationship with her. If he had

not rejected her it might have been an interesting relationship, but he

seemed to have little forgiveness in his heart. I believe he missed a

great deal of joy.

Another ripple in the family circle of the Boultons and O'Neills may be

only on the edge, but still tangent to the immediate relatives. All of

this I have stitched together in telling how I believe many in the two

families related to each other, as well as presenting the tremendous

effect Gene O'Neill had on each one.

It would be a mistake to leave out the part of my own

life, which was certainly impacted by the shadow of O'Neill. He was the

reason I believed I could not become a writer. From the time I was nine

years old, with an old Underwood typewriter from my mother, I was

going to be a writer! I wrote poetry in those days, and sometimes a

childish mystery story.

I wanted to write children’s books when I grew up, and

illustrate them myself. As I grew into my twenties, I wrote several

plays, which went into a file. My relatives were a family of

writers and artists, which definitely influenced me. The writers

included my father, Kenneth Thomas, my beloved great-aunt Margery Bianco,

her poet husband, Francesco, Agnes Boulton O’Neill, Barbara Davis, young

Cecil Boulton, my step-father Louis Colman, his later wife Hila Colman,

and of course, Eugene O’Neill. I was surrounded with writers and quite a

few artists, including my grandfather, Edward W. Boulton, cousin Pamela

Bianco, and Edward Fisk. Oh yes, I thought it was the natural way to go.

I was born just before the O’Neills divorced and a short

time after my mother had been involved with their family, so as a little

child I heard much talk of Gene O’Neill. Of all the writers in the

family, O’Neill loomed larger than the others, seeming the most

impressive and the most famous. He became the “Great God of Writers” to

me. Also, I was very aware my family did not care for him as a person

and he was an abandoning father to Oona and Shane, as my father also had

been with me. The impact was devastating.

Gene O’Neill impressed my mother, her sisters and my

grandmother, and they basked in the light of his fame, though it was

obvious to me that none of them really held any respect for him as a

kind and good human being. They did respect the fact he was brilliant, a

genius, psychologically aware, attractive though moody, and a great and

famous writer…but the family did not like him.

For me, O’Neill was an inspiration, another writer with

whom I could identify, but at the same time being so awesome, he was

untouchable. The conflict I held was in realizing, though Gene O’Neill

was an inspiring writer and had attained great fame, no one in the

family really cared for him. As a child and a young person I had

connected these two things: If I became a writer no one would like me! The conflict became overwhelming and I turned to music, which

was safe and comfortable. The music offered me a place to take my life,

and perhaps enjoy more social times than being a writer would have

allowed.

Another facet of the O’Neill connection was the shock of

realizing how much of my identity was indirectly tied up with this man

and his family. My mother and grandmother were also under his spell, and

I inherited the problem. As a child at the close of this notable decade,

the ten-year relationship of Aggie and Gene, I picked up a large part of

the drama and added it to my persona. It became an important part of my

identity, though I could not admit it, even to myself. Facing this in

later years was very painful. I had allowed the problem to run riot with

my hopes of becoming a writer. It took half a lifetime to recognize and

work through the conflict.

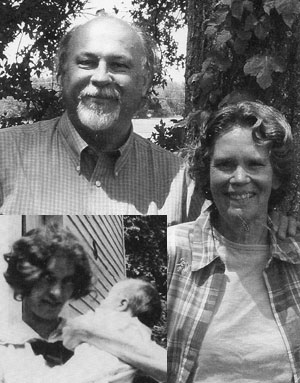

|

Kerry and

Maura O'Neill Jones.

Maura's father Shane with

his mother, Agnes, 1920. |

A few years ago my cousins, Maura and Kerry Jones,

invited me to an O'Neill gathering in the New London home where James

and Ella O’Neill and their two young sons, Jamie and Gene, had lived for

many years. When I walked into the Monte Cristo Cottage, there was Gene

O'Neill in all his moods, facing me once more. I knew immediately why I

resisted for so long going down to the Connecticut shore to see this

house where Shane and Oona’s father, Aggie’s ex-husband and my uncle by

marriage, had lived as a boy. Eugene Gladstone O’Neill was there, not

only on the walls in many photos, but in spirit. I could feel his

presence.

Feeling an intense anger surge up, I knew once more I

had to deal with the strong emotions brought up by his face, his name. I

had grown up seeing the hurt and the pain of his children who were dear

to me. I too had felt the same pain of abandonment with an absent

father, and O’Neill represented that picture in my mind. I had heard the

adults talking over and over about his ways, his brilliance, his fame,

and his unkindness and selfishness. I had seen several lives

considerably hampered or destroyed because of his selfishness.

Having been on the fringe of the “ misbegotten,” I am

deeply grateful that with help I have not been destroyed by it. It took

many years to let go of the O’Neill books and pictures I had acquired

from my mother. It was as though if I did this I would lose a part of

myself. To finally look with honesty at the importance I had attached to

being involved indirectly with Gene O’Neill and directly with his family

had been a very painful realization — but cleansing and releasing.

Now was the time to let it go, not just the attachment

to books and relationships, but to my not allowing myself to become a

writer. It began to clear and I felt as though I had finally faced the

dragon. The gathering in New London at the old O’Neill home was

impressive and included many people with a deep understanding of the

O’Neill drama. I felt at home with them. I was healing and realized I

had needed to see all the pieces and then complete the picture.

Hearing about and watching the children of Shane and

Oona grow into strong, interesting and productive adults has been a

delight. They may have their own ghosts, but they appear to have shed

the shadow that hung for so long over the heads of the O’Neill family

and the Boultons connected with them. I am impressed with the lives they

have made for themselves and their children. They take an interest in

their heritage, but are not dominated by it. To me they are like a

beautiful border on the tapestry woven from the threads of two families.

It seems there are few left in the family to hold

memories or strands of this colorful weaving in which the Boultons and

O’Neills have been joined. These lives, in many different ways, have

been woven together for the better part of a century. Now seems the time

to tie off the ending threads.

May the children who remain look back and be touched in

a gentle way and with a deeper understanding of those sometimes sad and

sometimes beautiful distant families.

The ghost of Eugene Gladstone O'Neill has walked among

us, and I have been one to keep this ghost alive within my mind all

these years. Now I would like to put this, with all the stories, quietly

to rest.

It has truly been a lifetime learning experience. I now

feel very close to all these characters cast in my particular drama.

The tapestry, for me, now hangs completed.

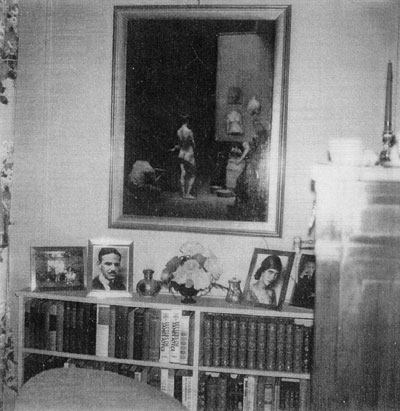

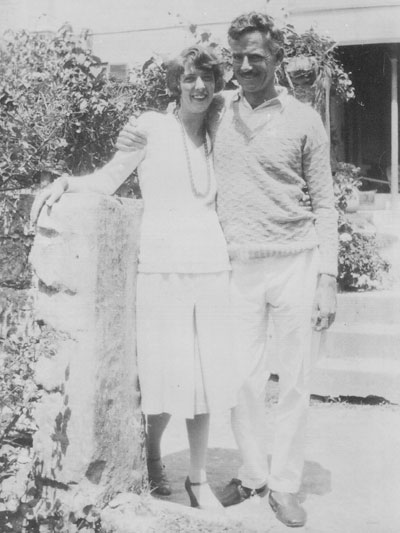

|

| Budgie and

Gene in Bermuda, 1926. |

|