|

Chapter XVI

The year after Oona left, we had a frightening

experience involving Jimmy Delaney who was living with Agnes in The Old

House. Our last days on the Herbertsville Road in West Point Pleasant

were right after a night when Jimmy, drunk and angry, came roaring over

from next door. He broke the glass in our front door, threatening Nanna.

He and Nanna had had an argument earlier in the day. (To this day I do

not know what it was about.) I was asleep in bed and a scream from my

mother woke me up. I ran downstairs to see what had happened. Mother

wasn’t there and I thought she had been killed.

Nanna stood on the porch, in the midst of all the broken glass, with

blood on her dress. Jimmy had gone. It was a nightmare for a

twelve-year-old. Our family was very quiet and reserved, and things like

this happened only in bad movies.

Nanna quieted me and said she cut herself picking up pieces of glass and

Budgie had gone next door to phone the police.

“Run upstairs and tell Robert everything is o.k.” Nanna sounded

shattered.

I found my little brother sitting up in bed, crying and frightened. I

told him everyone was all right. Mother came up to be with him and

anxiously asked me to run up the road and see if Homer would come down

and help us. Homer and Gerda lived three blocks up the road, and as well

as being dear friends, Gerda had been giving me piano lessons. My

emotions were on hold as I left Mother consoling Robert and Nanna

clearing up the glass downstairs. I ran very fast up the dark road which

seemed miles long.

“What are you doing here so late in the evening?” Homer asked as he

opened the door to me. I couldn’t speak. He leaned down to hold me, and

it was like a dam bursting. Totally shaken, I tried to explain, but the

words wouldn’t come out. I was in shock and both those dear people

comforted me until I could explain. “Please go down and help them! Jimmy

broke our door and they need you to help!”

Homer drove his car down, gathered up the family, and we stayed with

them overnight. I lay in bed on the porch with my grandmother, still

terrified and unable to sleep. That awful scene ran over and over in my

head for the rest of the night. If Aggie and Oona had been home this

would not have happened.

The next day we moved into a rooming house until we were able to move

into a house Mother found across the river in Brielle. We never went

back to the yellow ochre house again. I was glad to be gone from there

because I missed Oona so much, and it was easier to deal with this

hurtful loss in new surroundings.

My brother told me years later that he kept track of Jimmy whenever he

was around because he wanted to protect the family from anything like

that frightening night happening again.

During my first two years in high school, Oona was busy being a

debutante and enjoying the New York scene with her mother and brother.

The Second World War was still raging, and the U.S. had become involved.

It was a strange and difficult time. We were fingerprinted at school and

made to go through drills in case of war emergency, probably because of

living by the coast. Many of our older teachers left to go into the

service or take factory jobs and were replaced by new, younger teachers.

Friends in school were losing fathers or brothers in the overseas

fighting.

Oona and I were not in touch those two years, but I read the New York

papers and

kept up with what she was doing. She joined Shane at the Art Students

League in the city for a short time, but decided it was not for her.

Gene and Agnes wanted her to go

to college, but she refused. Shane continued studies at the League, and

became an accomplished sculptor. My brother and I remember the handsome

horses he sculpted later on in Point Pleasant.

Oona began moving in cafe society, taking part in war work, and I began

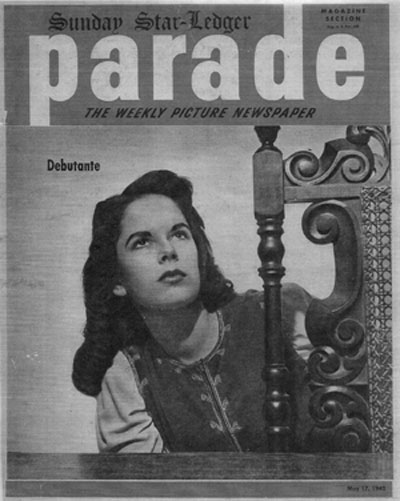

collecting news clippings. One page from the press showed Oona at the

Stage Door Canteen for servicemen. Another described her activities when

she was photographed as Debutante of the Year at a Russian War Relief

benefit, held at the Lafayette Hotel in Greenwich Village. The picture

was nationally syndicated. But my favorite ones were from The Sunday

Star-Ledger “Parade” section.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

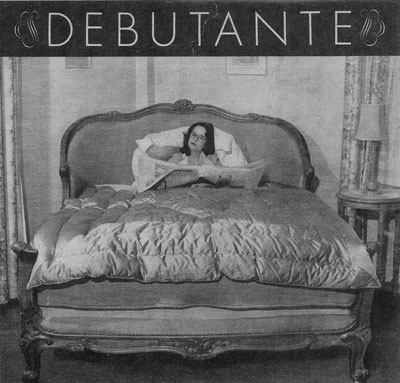

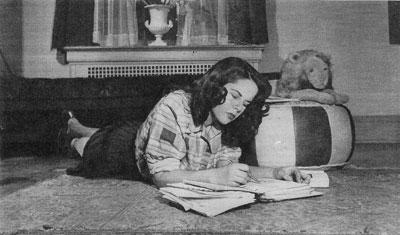

Four page “Parade” story of Oona's debutante days in 1942. |

Then came the magazine ad where Oona had been photographed for Pond’s

face cream. Budgie told me how angry Gene O’Neill was over this; he

thought it was cheap and beneath her. Perhaps, but she was busy in the

war effort and from my fifteen-year-old perspective, doing all kinds of

good and interesting things. Her mother also was very supportive.

Oona was in another world...and so very beautiful! I had heard she

wanted to go into theater and become an actress. She tried out and was

accepted for a part in the stage play of Pal Joey, to be held in the

Maplewood Theatre in New Jersey. The play was a failure, and Oona went

to Hollywood with her friend Carol Marcus. Aggie went there shortly

afterwards to do some screen writing.

Oona stayed in California, which again seemed so far away. After her

eighteenth birthday she signed up for a part in The Girl From Leningrad.

Her trial part as the lead was not successful. Next thing I heard, she

was to marry Charlie Chaplin!

The marriage of Oona O’Neill and Charles Chaplin made headlines in every

paper across the country. The big story was the thirty-six year age

difference. She was just eighteen and he was fifty-four. I didn’t care.

I just wished the reporters would leave her alone, and if they were

happy, what difference could it make? At sixteen, I was a romantic and

it all seemed quite exciting! My cousin Oona marrying Charlie Chaplin! I

laughed when I thought of our rollerskating and imitating Charlie in

Modern Times.

Suddenly I began hearing from Oona again about Charlie and her new

life. It was thrilling for me and the letters flew back and forth. Next

thing I knew she was coming back to New York. Oh, how I wanted to see

her.

Oona called to arrange a meeting in New York, and I was off on the bus.

I found their apartment and met Charlie, who entertained me while Oona

prepared herself for our lunch in town. Charlie described a recent

evening with some very comical character who had performed a song and

dance for them in a local club. He grabbed the cover from his breakfast

plate and donned it as a hat, proceeding to dance around the room. I was

a delighted audience!

Our lunch was at Club Twenty One. It was most impressive to a

sixteen-year-old girl from a small town in Connecticut. I had my first

vichyssoise and enjoyed watching the waiter wander around with a

bun-oven hanging over his shoulders, offering guests assorted hot

biscuits and pastries.

We talked about all the things that had happened since we had last seen

each other. Oona had much to tell. The most fascinating story was about

the F.B.I. having gone into her apartment in Hollywood just before her

marriage to Chaplin. The two F.B.I. agents made Oona sit in a chair

while they searched through bureaus, closets and boxes to see if they

could find anything that might incriminate Charlie. The F.B.I. had been

trying to find some reason to deport him. Aggie confirmed this and added

a rather bizarre tale involving William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper

king and owner of many big newspapers in the country.

The story went that Hearst was jealous of Chaplin, who had at one time

carried on with Hearst’s sweetheart and mistress, Marion Davies. Davies

was a showgirl turned actress, and Hearst lived with her in his Castle

at San Simeon, California, while his wife lived in New York. Hearst

engaged in such a tirade against Chaplin, with false claims about

the Joan Barry paternity case and trumped up stories of Charlie’s being

a communist, that the F.B.I. began to look into his private life. Hearst had

the reputation of being able to destroy anyone he did not like.

Charlie later told Aggie about almost being shot by Hearst, and Aggie

told the story to me. It seemed that Davies and Hearst gave a grand

party on their luxury ship, which was moored off the coast of San Diego.

This was in 1924, and Chaplin had been one of the guests. He had

described the entire scene to Aggie.

It had been during the time of prohibition in the United States, but

Hearst's large yacht, the “Oneida,” illegally carried Canadian liquor

and fireworks. Hearst had on board a set of pistols he used to take

potshots at flying seagulls. During the second evening of the party,

Hearst became extremely angry with Chaplin for flirting openly with

Davies. Flying into a rage, according to many stories, including

Charlie’s, he shot or had one of his guards shoot someone he thought was

Charlie. It turned out to be Thomas Harper Ince, a film producer, who

from the back closely resembled Charlie in looks and stature.

Hearst's doctor reported the wound as a case of “acute indigestion.” The

true cause of Ince's death was kept a secret, and the gunshot wound was

not reported. Two doctors were involved, a Dr. Steinbeck and Hearst’s

private doctor, Dr. Goodman. Ince was carried off the yacht, and

Chaplin's driver Kawa recalled seeing what looked like a bullet hole in

his head as they carried him unconscious down the gangplank. Ince was

taken home, where he died and was cremated immediately. The reports in

the papers, controlled by Hearst, told only the story of acute

indigestion, and to this day it remains a mystery to the general public.

Charlie was fortunate to have come away unscathed. Poor Tom Ince was not

so fortunate. It was said that Hearst made certain no one discussed the

entire event in any way and he conveniently kept much of it out of the

papers.

In later years, Hearst's granddaughter, Patricia Hearst, together with Cordelia Frances Biddle, wrote a book called Murder at San Simeon, which

dealt with the bizarre story.

Oona seemed to enjoy the excitement of these stories, and so did I. We

spent the rest of the afternoon sharing adventures. Oona put me on the

bus back to Connecticut where I was living with Budgie and the family

and going to school. She stood waving to me as I left and somehow I

knew, once more, it would be quite awhile before I saw her again. Oona

and Charlie were going back to California.

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVII |