|

Chapter XIV

In 1934 my family and I moved from Connecticut to West

Point Pleasant, New Jersey. The trip was made in the old blue Buick,

loaded down with our belongings stuffed into a large trunk and into

every available corner of the car including the running board racks,

which were filled to the brim. I was most excited because we were going

to live in a house near Oona!

|

| Budgie,

1927 |

|

| The old

Buick with Budgie, 1927 |

On the way down to Jersey we traveled over the Bear

Mountain Bridge, which spans the Hudson River. Just as we crawled over

the top of a very high part of the hill the car stopped and wouldn’t

move. Oh no...out of gas! Budgie trudged down the mountain with a can

for gasoline and we watched as she disappeared out of sight.

Nanna, sitting in the back with Robert and me, began to

sense our restless anxiety. “Do you know why this is called Bear

Mountain?” Nanna asked us. By the time she finished her wild tale about

the bears in the hills, we were thoroughly frightened, and silently

crawled under a large car blanket so the bears wouldn’t see us. This was

her clever way of keeping us quiet! Then I began to worry that Mother

wasn’t back because a bear had found her, but finally she returned

intact, with a kind man from the gas station who helped her fill the gas

tank, and off we went.

In West Point Pleasant we settled into a small

brown-shingled house on Faltot Street, a block or two from Aggie, Oona

and Shane, and here we lived for about a year. Then Aggie wanted Nanna

to be close by to help with Oona when she had to be away, so she bought

a house for us, next door to The Old House on the Herbertsville Road and

we moved again.

|

|

The ochre house next door to

The Old House, 1936. |

|

The Castle

Tree in Oona's yard, 1936. |

We loved the ochre-colored house. There were big

bedrooms for each of us, and a wonderful large living room and dining

room separated by a hall. In the hall was a huge grate for the furnace

heat to rise, and it blew wind up at us when we walked across. If we

played marbles on the nearby rug, the marbles would often roll down into

the little grate holes, to be gone forever!

The Old House next door was warm and comfortable and a

favorite place for me to go and visit because it always felt like

family. There was a large fireplace and on special occasions Aggie would

bring out a great bear rug so Oona and I could sit on the floor in front

of the fire. I well remember grand Thanksgiving dinners in the somewhat

formal dining room, served by the cook-housekeeper, Anna Gerber. Anna

and her brother, Dan, who helped with the outdoor chores, lived a short

way up the road.

A round, plump lady with a ruddy complexion, Anna was

always ready to tell you that things were worse with her than with you,

if ever she heard you complain. If one of us told Anna we had a stomach

ache, she came back with “ Me too, Missus!” and then the story of her

stomach ache. Oona and I loved old Anna and spent lots of time in the

kitchen chatting with her, eating her cookies and playing with the many

cats who lived much of the time in the connected back shed.

Growing up together, Oona and I had a strong bond with

each other. Besides being cousins, we were fatherless children. My

father, Ken Thomas, came to visit at times but there was for many years

a mystery connected to him. As related earlier, I did not know he was my

father. Oona's father existed in her life, but lived far, far away. She

seldom saw him, and he did not seem very interested in her.

Sometimes Oona was also a motherless child during those

seasons when her mother needed to be away for months at a time. Her

brother was away in boarding school and Oona would stay next door with

Nanna in The Old House, or with our cousins in Connecticut. I loved the

times she was next door to us, but I'm sure now she must have mourned

deeply for her own scattered family.

As my mother’s oldest sister and my aunt, Aggie was a

very strong influence in my life. I knew she had married Eugene O’Neill

and was with him for ten years before their divorce in 1928. To me she

was “Aggie,” but I always remember her as “Mrs. O’Neill” to others, and

it gave her an air of importance, which I had sensed at an early age. I

was old enough, when we moved next door, to become very impressed with

the great O’Neill. Though totally absent, he was still the once-husband

of my adored Aggie, and father to Shane and Oona.

I remember Aggie as tall with wavy dark hair and large

blue eyes, also a mole on her chin, which somehow didn't seem

unattractive. Her mouth was full and soft with a warm, relaxed smile

that might change in a flash to a hard, angry look. Even though I was a

little frightened of her at times, I wanted so much to be just like her

when I grew up. She seemed to be admired by everyone, and to have

everything she wanted or needed. That was what I believed.

Aggie also seemed wealthy, driving a car with leather

seats and living in The Old House which was long and rambling, and where

Anna did all the cooking and housekeeping so Aggie could write. Aggie

always found change in her pockets and was able to travel to exciting

places like Bermuda, and do interesting and romantic things. All of

this, I believed, was because she had been married to Eugene O’Neill and

she was still connected to him in some way, and famous because of it

even though Jimmy lived with her.

|

| Agnes with

Jimmy Delaney, 1937. |

|

| The Old

House on Herbertsville Road. |

Jimmy Delaney, a newspaperman from Troy, New York, was

on the scene before Aggie went to Reno and for the years I well

remember. He lived with Aggie but she wouldn’t marry him. We understood

later that she would lose her support from Gene if she married again. I

remember Jimmy being a short, heavy-set man who loved to play golf. In

the summers he wore white pants and shirts, and in the winter he donned

a brown tweed jacket and wore knickers with argyle socks, all of which

fascinated me. He was quite friendly, but didn’t pay a lot of attention

to us as children, unless it was to drive us to the beach when Aggie was

busy.

When Jimmy took care of Oona at the time Aggie was

getting her divorce from O'Neill, he used to call her “Oona Ella

Oleander Banana-oil O’Neill,” which she loved as a little child. By the

time she was eight she considered it teasing and the name faded. It had

been an affectionate, playful joke because she was born in Bermuda where

the oleanders grow.

Those were the days when I was becoming more and more

aware of the O’Neill connection. Not only with living next door to

Agnes, Shane and Oona, but also from the many conversations I listened

in on between Mother and Nanna. They spoke often of the days when Budgie

had worked for O’Neill, typing his manuscripts, being a part of the

family, living with them off and on. She also talked about the

gatherings of artists and writers she had met with the O’Neills, writers

such as Harry Kemp the poet, Mary Heaton Vorse, Ted and Genevieve

Taggert, and others connected to the Wharf Theater. Budgie had so much

enjoyed being a part of that scene.

There were stories from those early days in

Provincetown: of Bobby Jones, Susan Glasbell, Jimmy Light and many

others. These stories I can no longer recall. Only the names of the

people linger in my mind, where they all seemed to have an importance

about them. Budgie talked of Mabel Dodge, an artist and writer, whom she

especially liked. Dodge had owned the Coast Guard Station at Peaked Hill

Bars before the O’Neills, and decorated the place very tastefully.

Budgie especially loved the wicker furniture with cushions in white and

yellow, sporting blue trim. I often thought Budgie would have loved

living in that house by the sea forever.

After my family was established in the ochre house next

door, Oona and I became very close. I have many memories of our times

together, both fond and confused memories, rainy day memories and warm,

blueberry memories of walks down the road to the river.

At the south end of The Old House, where grandfather

Teddy had built two large rooms, was a landing on the stairway to the

second floor with a stained glass window. On sunny mornings, Oona and I

often sat on the highest stair to watch the soft, pastel colors

magically reflecting off the walls.

I loved going into Aggie’s room at the top of the

stairs. It seemed so grand with the huge, carved walnut bed, her writing

desk and a table with carved legs and heavy marble top. These had come

from the Boultons when some of grandfather Teddy’s family moved from

Philadelphia to Riverton, New Jersey. They were a part of Aggie’s

inheritance because she had been fortunate enough to have been named

after Teddy's sister, her Aunt Agnes Boulton.

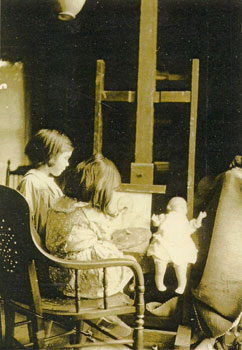

Teddy had also added the large studio with a skylight,

and double French doors going out into an expansive back yard. The worn

but sturdy easel, which Teddy had used for so many years still stood at

one end of the studio when we were children, and long after he was gone.

This favorite room became a place where Oona sometimes gave parties, and

where, on rainy days, we spent hours painting pictures at the easel,

listening to old records, singing along with Rudy Vallee and trying to

copy his nasal tones.

|

|

| Oona and

Dallas at Teddy's easel. |

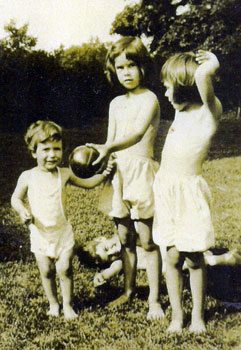

Robert,

Oona and Dallas, 1936.

(Unknown boy on ground.) |

|

|

Cousins Jim, Jeane and Marge

Sheldon with Oona. |

When Gene and Aggie had stayed in The Old House years

earlier, Gene had built a rough tennis court in the back of the house by

the old barn. It was pretty well gone by the time I lived next door, but

Oona and I played many games of Hopscotch on the remains of the hard

ground.

|

|

| Hopscotch

game, Oona and Dallas, 1936. |

Then there were the special rainy days when we put on

our slickers and walked barefoot to the Manasquan River, where rowboats

anchored along the beach were empty and enticing. We would sit in one

and pretend we were out on the water. One day in the spring, we thought

it was fun to push each other off the boat and fall into the water. At

home we told Nanna we had fallen in, while aside to each other we

giggled... “accidentally on purpose!”

We were nine and eleven when Oona and I decided to start

a poetry club. We would learn “by heart” one poem a week. Nanna was

delighted to be our audience as we recited them to her. One of my

favorites was an Elizabeth Barrett Browning poem, which Oona and I both

learned. There was a line we played to the hilt— “Why you who would not

hurt a mouse can torture so your lover...” Another poem which I

presented, went “Oh what can ail thee knight at arms, alone and palely

loitering...” I exuberantly recited “Oh, what can nail thee, knight at

arms...” We did impress our grandmother.

|

|

| Oona and

Dallas, West Pt. Pleasant. |

Oona,

Dallas and Middie dog with friend, 1936. Matching coats and

hats made by Nanna. |

Nanna sometimes told us stories, and one of our

favorites was about Black Bart. It was a favorite because Nanna said he

was a relative. He was a kind of Robin Hood in the eighteen hundreds and

became a legend, a folk hero, in the history of California. We were told

never to say a word about him to our very prim, elderly Aunt Agnes (Teddy's sister). She was extremely distressed about the family

relationship to a robber! He was Charles Edward Boulton and had come

from a wealthy Philadelphia family. It was on a white-hot day in July 26, 1875, near

Copperopolis, California when Black Bart held his first stagecoach

robbery. He was out-fitted with a flour sack over his head, a dirty

white duster to conceal his build, and rags tied around his feet to

eliminate the possibility of being identified by his footprints.

The story was that he walked out of the sage-brush with

a double-barreled shot gun and stopped a stage coach, demanding that the

driver hand over his gold. He wanted none of the jewelry from the ladies

on board, only the gold from the Wells Fargo Company. He always left a

poem at the scene of the crime.

“I've labored long and hard for bread,

For honor and for riches.

But on my corns too long you've tread,

You fine-haired sons of…!

Then signed, Black Bart,

the Po8

The stories of Black Bart spread worldwide and he

became a folk hero because he never robbed passengers, only the giant,

moneymaking Wells Fargo Company. In almost thirty robberies he never

once pulled the trigger of his shotgun, and some believed it wasn't even

loaded. Eventually he was caught through a laundry mark from a

handkerchief he dropped at the scene of a robbery, and Black Bart spent

a short time in prison. There is no accurately recorded history of his

life after this.

Nanna was a good storyteller, and this was one of our

favorites.

Saturday afternoons were movie times, so Oona and I would walk into town

across the Canal Bridge to meet our two friends, Mavis and Amada

Williams, and go to the show in Point Pleasant. Oona sometimes treated

me, which was fun because then I had a nickel from home to buy candy.

However, when I had enough money to treat Oona, she would refuse.

Looking back, I had strong feelings about that and felt hurt. I wondered

years later if it was her way of telling me she had something I didn’t

have. She had money.

One Saturday on our movie afternoon, when I was ten and

Oona was twelve, we went to see Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times.

Our favorite part was when he rollerskated, kicking himself on the

bottom with his free foot. Actually he was dancing on the skates. After

the show, we walked back home and pulled out our rollerskates. Out on

the road we tried to imitate Charlie, and laughed our way up and down

the street. Little did we dream that one day, only six years later, Oona

would marry him!

Both avid movie fans, and buying movie magazines when we

could, Oona and I kept scrapbooks of our favorite stars. I adored Errol

Flynn who at the time seemed handsome, and I thought Olivia de Havilland

was the most beautiful of all the stars. Oona kept pictures of Nelson

Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald. Oona wrote a fan letter to them and was

overjoyed when they responded. Their letter was her favorite treasure

for quite awhile.

Other memories that we chuckled over later on were the

times when great-aunt Agnes came to visit. As mentioned earlier, she was

grandfather Teddy’s sister and seemed very old. Our mother told Robert

and me that Aunt Agnes was visiting and wanted to see us. Therefore, we

would need to wash our hands very carefully and go over to The Old

House, where she would be staying for a few days with Aggie and the

family. Because she had been made to go through it earlier, Oona was

allowed to stay inside and watch the suffering scene through the window.

Aunt Agnes would be sitting in one of the large wicker

chairs on the porch. Very elderly, with soft white hair pinned up on her

head in a loose top-knot, and pale blue eyes behind silver-rimmed

glasses, Aunt Agnes looked very severe as she greeted us. Then came the

distressing part as we had to go up to her while she inspected our hands

and fingernails to see that they were clean. Poor little Robert had to

bow as he made his exit and I had to curtsy. It was so embarrassing!

Another time which stayed in my mind for years was when

Oona and I were looking at things in the local Woolworth's “Five and

Ten,” and we stood at the cosmetic counter. Oona loved looking at the

nail polish and the lipsticks. She turned to me and whispered, “Why

don’t you take one of the bottles of nail polish? No one will see you.”

All I could think was that she was telling me to steal something. I

never wanted to say “no” to her....I was so afraid she would be angry

with me. I remember wrestling with this for a moment or two. I just

couldn’t do it. Oona was disgusted with me, but I told her I could not

steal something. We walked home in silence. Later on, I wondered why she

had wanted me to do that. Why didn’t she take it herself?

Oona went to visit her father and Carlotta at Tao House

in California only once that I can remember. I felt as though she were

afraid to go, but didn’t want to say so. I also had a feeling she was

nervous about seeing them both. She had liked Carlotta, her step-mother,

who had been kind the first time they met, but she wasn't sure about

this time. Her father seemed awesome and had become such an important

giant to her that it must have been difficult. He was wealthy and famous

and not very available. He seemed quite removed from her life and seldom

wrote to her...mostly little messages through Shane. When she came home

from the visit she did not want to talk about it with me, but retreated

to her small cottage in the back yard, wanting to be alone. On Oona's

last birthday, Aggie had had the little building made into a special

place for her. It was charming, with bookcases, a window seat and a

Dutch door. After a short time alone in the tiny house, Oona seemed to

feel better and quickly slipped back into the routine of school, play,

friends and our fun times together.

Looking back, I can see the disturbing times Oona had,

over and over. There was one early summer evening when we wanted to go

to town across the Canal Bridge. We went in the house to ask Aggie if

Oona could go. Aggie and Jimmy were sitting at the long oval table in

the dining room, with glasses of sherry in front of them. I do not

remember Aggie drinking a great deal, but I was told later on that

sometimes she would binge and then go away for a week or more to

recover. Oona must have been more aware of these times than I was. This

was one of those scenes where I can still see the hurt and pain on

Oona's face as she asked, “May I go to Point to the drugstore for ice

cream?”

Her mother responded in a wobbly voice, “Go do whatever

you want...” and shooed her off with a wave of her hand. Jimmy stared

off into space and didn’t say a word. The drinking was something I was

too young to comprehend, and I wasn’t living with it. Because of Oona’s

reaction, I felt it was serious and seemed frightening.

We left the house. Oona couldn’t talk about her

feelings. We didn’t go into town as we had planned, but went to sit in

her playhouse in the back yard. I tagged along as Oona went inside and

sat in the window seat, where she looked sad and didn’t want to talk. I

went home to write a note to her and put it in our secret tree we called “The

Castle,” a great elm that stood between our houses. The tree had two

trunks with a small hole in between which was good for notes or secret

messages. I thought perhaps a note would make Oona feel better.

Chapter XV

Chapter XV |