|

Chapter I

My cousin Oona and I have a history going back to 1918

when an O'Neill and a Boulton married and began an unforgettable story.

Agnes Boulton and Eugene O'Neill married on April 12th of that year and

thus began a marriage lasting only ten years, but a relationship which

affected many. The pictures in my mind of the two families which have

shaped the lives and times of Oona and me and our families, may help to

offer a colorful history with three generations of O'Neills and

Boultons.

Eugene O'Neill was a household name. When he married

Agnes Boulton, my aunt and my mother's oldest sister, he became my uncle

by marriage. He was the father of my cousin Oona, who lived in The Old

House next door, and of Shane who came home every summer and played big

brother to both of us. This Gene O'Neill was very famous and very

brilliant and wrote plays the family all talked about. He was also not

very nice and not very kind, and the family talked about that.

My mother, Margery Boulton, often brought up stories

about the older O'Neills in Eugene's family. This included the

illustrious actor James O’Neill and his wife, Ella Quinlan O’Neill.

Along the way someone had given Margery an old trunk belonging to James

O'Neill. Famous for his role as Edmund Dantes in The Count of Monte

Cristo and playing the same role for twenty-nine years, the popular

actor traveled constantly. His steamer trunk with JAMES O'NEILL stamped

across the front, had white panels under the bentwood bands around it

for strength, and displayed a large brass lock on the lid. According to

my mother, the trunk went with him, holding his clothes, costumes and

belongings. Gene and Agnes found themselves with the trunk after James

O'Neill died, and because Margery had admired it, they offered it to

her. I inherited the trunk from her, and in the attic of my house it

stored special books, papers and precious photos from both families.

Little did I know while I carried the great old trunk with me on my

journey, I was hauling O'Neill ghosts along with it. The trunk

eventually disappeared, but I do believe the ghosts did not go with it.

The spirits of Eugene O'Neill and his family stayed with us.

James O'Neill's fear of being poor and thus remaining in

one profitable acting role for six years before branching out into other

roles, had a negative effect on both his sons. Going from city to city

with the plays meant constant traveling, which was very difficult for

all the family. Ella’s battle with a drug problem (caused by the use of

morphine during an ailment from Gene’s birth) brought about guilt in all

three men in the family. The effects were that Jamie and Eugene both had

alcohol problems and tended to squander money. Margery had known them

both. Jamie never married and died at an early age. Eugene reached a

point where he attained fame and fortune, and, thankfully, his addiction

to alcohol turned into an addiction to writing. Gene had determined,

early on, that he was incapable of writing when he drank. The writing

eased the pain and guilt he carried, and came before everything else.

His deserted family aside, we can be grateful for the amazing theater

and philosophy he left to us.

And what about these Boultons who are included in the early chapters and

the indexes of almost every book written about Eugene O’Neill? Who are

they? This family is the other half of Shane and Oona O’Neill's

heritage. Edward W. Boulton, his wife, Cecil Maud Williams, and their

four daughters were a most interesting and intriguing part of the

family. Theirs is a fascinating history starting long before Oona and I

were born.

Edward William Boulton, our grandfather, was a son of

the Boultons from Philadelphia who, with a family named Dallett, made

their fortune from the Red D Line of passenger ships, which ran between

New York and Curacus, Venezuela. A short history tells us that the

Boulton, Bliss and Dallett Company operated services to Venezuela under

a white flag with a large red D in the center, for the Dallett family

who had originally founded the shipping line. The Red D Line started in

1820 and is still considered to be the oldest and longest running

merchant shipping line in American maritime history. The Bliss family

were partners through marriage to the Dalletts, and the Boultons were

the Venezuelan agents to the company.

|

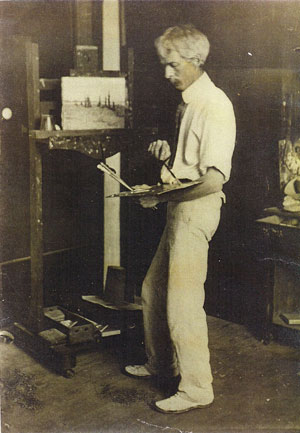

Edward W.

Boulton at easel, circa 1920. Courtesy of M. Boulton collection. |

Edward Boulton, or Ted, as he was called, was a tall,

lean and homely man bearing a strong face with high cheekbones. His kind

eyes lent a gentle expression to his demeanor. Ted’s great love was

drawing and painting, and he considered himself fortunate in being able

to study with the radical Thomas Eakins. Eakins shocked the art world in

those Victorian days by using both male and female nude models in his

classes, and dissecting cadavers, from which his students studied

anatomy. My mother told a funny story of finding a pickled finger in her

father's coat pocket at one time, after his return home from the Art

Students League.

Eakins considered Boulton a protégé, and when he was

forced to resign from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1886,

young Edward joined with him and a group of serious students in founding

the Philadelphia Art Students League, with Ted serving as their first

president. Over the years he helped Eakins with a commission executing

the death mask of Walt Whitman, and later posed for The Cowboy of the

Badlands, which today hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New

York City. The museum houses an entire section devoted to Eakins and his

work. We had a working drawing of The Cowboy, which stayed in a box for

years, and then, through the decision of my mother, went to auction and

a private collection. I chuckle as I think of taking it down to New York

for my mother, and carrying it through the streets in a canvas bag on

the way to our destination.

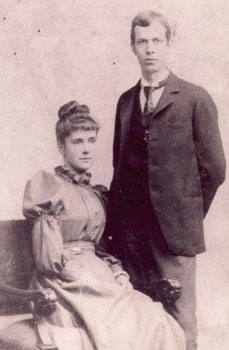

It was during those days at the Art Students League that

Edward Boulton, or Ted, met and married Cecil Williams in 1891. Their

oldest daughter, Agnes, married Eugene O’Neill. Barbara and young Cecil

(II) were the middle sisters, and the youngest daughter Margery, was my

mother. I was born just one month after Edward Boulton’s death in 1927.

It saddens me to think that he did not live long enough for me to know

him as a grandfather.

|

|

| Cecil Maud

Williams, 1890s. |

Ted and

Cecil's marriage, December 31, 1891. |

Our grandmother, Nanna, was one of the most interesting,

complex and mysterious women I have ever known. Cecil (pronounced Sessil)

Maud Williams was born in London, England, and after her father’s death,

moved with her mother, and younger sister and brother to the United

States. One younger sister, Ruby Agnes, had died earlier at age

thirteen. Cecil's mother, Florence Harper Williams, was the daughter of

the head librarian at Oxford University, and a free thinker in her day.

She was included in George Bernard Shaw's The Intelligent Woman's

Guide to Socialism and Capitalism, and was one of the educated women

who were celebrated by Arnold Forster, writer, lawyer and longtime

influential journalist. Mrs. Williams was also a fan of Mme. Blavatsky

of The Theosophical Society and A.P. Sinnet, editor of The Pioneer,

India's foremost paper, as well as author of a book on “Eastern

Buddhism.”

Cecil’s father, Robert Williams, who died at age

forty-nine, had been a brilliant Oxford Greek student. His story was

impressed on me often, as I grew up. He spent part of his life as a

barrister after taking his degree and becoming a Fellow of Merton

College, Oxford. He held liberal views concerning the education of

children, believing they should learn to read early and then have no

formal teaching until age ten.

Williams' circle of friends included Lady Wilde, the

Russells, Swinburne and the Rossettis, all intellectuals of the time.

Called “a man of extraordinarily brilliant parts,” he took to journalism

and was considered a scholarly contributor to such papers as The

Observer, The Daily Telegraph and The Standard. After

becoming dreadfully despondent when someone stole a special story he had

written, Williams left his family and eventually died an early death

from alcoholism on December 8, 1886. There is little left but memories

and two small clippings to tell his story.

After her husband’s death, Florence Williams, with her

three children, sailed for the United States. She had a family

inheritance, which enabled her to take the trip and purchase a small

farm. After a short time in New York City, they moved to Quakertown,

Pennsylvania, bought a farm and settled down. Farming was very difficult

work and the kind of life with which they had never dealt. It proved to

be too much for the little family, and making a determined decision,

they sold the farm and moved to Philadelphia, where city life was more

to their liking.

City life reflected the time when impressionist art had

made its way into the States with names such as Winslow Homer, George

Inness, Whistler, John Singer Sargent and Mary Cassatt. Thomas Eakins

was making a name for himself in Philadelphia. Buddy Bolden in New

Orleans had developed the sound of jazz, which was making its way slowly

north. William Randolph Hearst had begun his “yellow journalism,” and

was buying up small newspapers across the country.

The Williams family loved the busy life as they lived in the house next

door to a Jesuit monastery. Young Cecil was fascinated with the Church

and became a Catholic. I do believe there was also a fascination with

the charming young monks her mother invited to dinner every so often.

To help with the family income, Cecil took a position as a clerk in a

large department store, while the younger children were schooled at

home. Philadelphia was a city with many activities and opportunities.

Cecil wanted to earn something more than the department store offered,

as her meager salary was not covering all their needs. Unbeknown to her

mother, Cecil applied for a position as a model at the Art Students

League where Thomas Eakins was instructing classes. She told her mother

she was working overtime at the department store, while really she was

modeling for the art classes once a week. Her mother would have been

enraged had she known, but Cecil kept her secret from all the family.

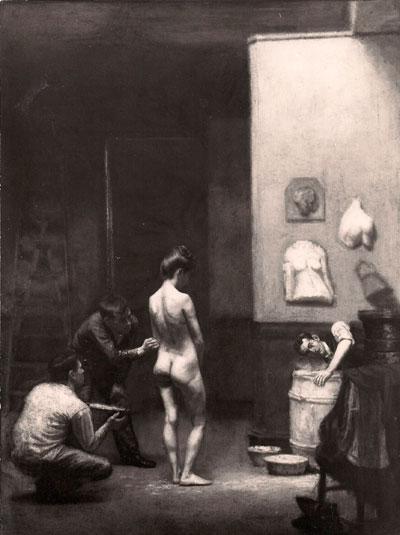

Margery and her sisters always believed their mother was the nude with

her back turned, being studied by a group of students and painted by

Eakins. Cecil would only smile a secret smile if anyone asked her about

it. The painting hung for many years in the family home at West Point

Pleasant, New Jersey. It was a gift from Eakins to my grandparents,

Teddy and Cecil. The painting was eventually given to Oona O’Neill

Chaplin by her mother, Agnes, and remains in Switzerland at the estate

left by Oona and Charles Chaplin for their children.

|

|

|

Thomas

Eakins painting, 1890s. Photographer probably E.W. Boulton. |

It was during this time when Cecil was modeling that Edward Boulton, in

his early twenties, attended classes at the League. He was very taken

with the beautiful young woman from England. With a tall, straight body,

she had a crown of upswept dark brown hair framing her small features

and soft hazel eyes. There was an appealing strength about her and an

air of mischief in her expression. Ted became very attentive and found

excuses to talk with her during their breaks.

Cecil was attracted by Ted’s attentions and a courtship ensued. She was

charmed with his gentleness and catching sense of humor, which

immediately endeared him to her. The young couple married on New Year’s

Eve in 1891. Their first child, Agnes, was born in London the following

autumn while they were on a visit to Cecil’s mother, who had returned to

England. She later became “Granny” to little Agnes, her first

grandchild. After they made the journey back to the States, the family

lived a year in Philadelphia. Eventually they moved to New Jersey and

bought The Old House on the Herbertsville Road in West Point Pleasant on

September 4, 1903.

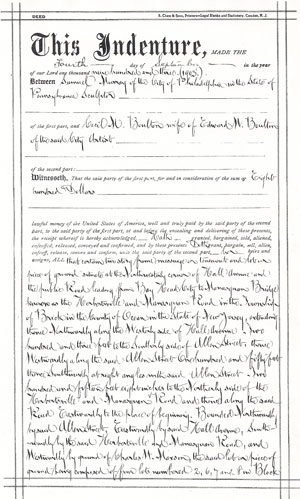

|

Indenture:

Purchase of The Old House in 1903. |

This was to be home to three generations of Boultons and O’Neills. Ted

and Cecil’s four daughters grew up there, near the Manasquan River and

two miles from the Atlantic shore. After Agnes’ marriage and divorce

from Gene O’Neill, she moved into The Old House with two of her three

children, Oona and Shane. Barbara Burton, the eldest, was in boarding

school and eventually went to work and lived in New York City in the

40s. Years later, Shane and his family would spend a number of years in

The Old House. (So many writers on books about Eugene O’Neill called The

Old House just Old House, which was not what we called it all those

years.)

|

|

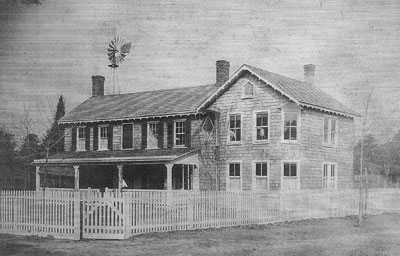

The Old

House in West Point Pleasant, New Jersey, 1893.

|

|

|

House before addition. |

According to Maura O’Neill Jones (Shane O’Neill’s daughter) and her

husband, Kerry Jones, Cecil and Ted first owned about two hundred acres

with The Old House. The land went to the canal on one side and over to

the Manasquan river on the other, then up what seemed a long way on the

Herbertsville Road. Whenever money became a problem they would sell a

few acres. Eventually there was left a little less than an acre around

the house. As time went by, West Point Pleasant grew into a suburban,

residential area. The Old House no longer stands. It was torn down to

make space for two other houses along the busy highway…the highway that so long ago had been a narrow dirt road used by a few horse-drawn

wagons.

Chapter II

Chapter II |