Eugene O’Neill showed early in his career his ability to

create controversy through his writing, and his 1924

play, All God’s Chillun Got Wings (Chillun),

was no exception. The last of his dramas to explore the

life of black Americans in the 1920s, Chillun,

which opened in May 1924, proved to be perhaps the most

controversial of these plays—others of which include

The Hairy Ape (1922), The Emperor Jones

(1920), and The Dreamy Kid (1918). While all of

these plays proved problematic in their portrayals of

race, especially by today’s perspectives, their

influence on the theatre and intellectuals of the day

cannot be ignored. O’Neill’s treatment of the black

experience in America is inevitably flawed, but his

attempts to create a voice for African Americans in

theatre—at a time when blackface was still the prominent

medium for depicting blackness in theatre and

movies—should not be overlooked. However, arguably the

greatest downfall of Chillun was in many of the

audience’s and critics’ inability to see beyond the

miscegenation and interracial kiss to a play about the

human condition, which O’Neill hopelessly attempted to

rectify. Prior to, during, and after the first

production of Chillun, O’Neill insisted that the

characters in his drama were much more than their skin

color, they were depictions of the greater human

condition. Unfortunately for O’Neill, however, his

inclusion of miscegenation and the infamous interracial

kiss between the main characters was the media’s only

focus. Much like his other so-called race plays,

Chillun has rarely been produced since its original

production in 1924 and even that production is outshone

by the controversy that surrounded it. The play was

generally considered a success, but the question of

whether the controversy surrounding it helped or hurt it

remains; while there were certainly large crowds who

came to the theatre to see Chillun, the reviews

of it were lukewarm at best. Due to the inconsistent

reception of Chillun, this paper endeavors to

argue that in reviewing the events culminating in

Chillun’s first production, it becomes clear that

O’Neill’s final race play made a lasting impact on

American culture for years to come, remaining a thought

provoking and controversial play to this day.

|

|

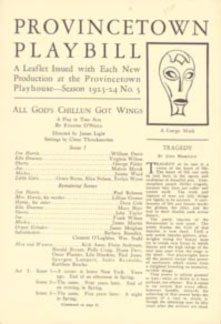

Figure 1: Playbill for the

original production of All God’s Chillun

Got Wings. The playbill included the

words to the Negro spiritual, “All God’s

Chillun Got Wings,” a poem by Langston

Hughes, and an article by W.E.B. Dubois.[1] |

Chillun is a play in two acts, which centers on

the relationship between Jim Harris and Ella Downey, two

childhood friends who eventually marry despite their

racial differences and the societal pressures of their

time; Jim is black and Ella is white. During the first

act of Chillun, O’Neill focuses on the evolution

of Jim and Ella’s relationship; in the first scene, they

are children, living in an interracial neighborhood in

Brooklyn, playing marbles with other children. As the

curtain falls on the first scene, the two children

discover they like each other, transcending racial

constraints—however, Jim promises to continue eating

chalk in order to become white, while Ella wants to don

blackface and become black. Nearing the end of the first

scene, Ella tells Jim, “I wouldn’t. I like black. Let’s

you and me swap. I’d like to be black. (clapping her

hands) Gee, that’d be fun, if we only could!”

However, as the next scene unfolds, which takes place

nine years later, Ella has succumbed to the racism of

the time, wanting nothing to do with Jim because of the

color of his skin. In the second scene, Jim asks Ella if

she hates him because he no longer speaks to him, to

which she replies, “What would I speak about? You and

me’ve got nothing in common any more.”[3]

In stark contrast to the prologue, this scene begins

portraying Ella’s struggle with her ideas of racial

superiority, which she fails to overcome. After being

abandoned by the prized fighter, Joe, and experiencing

the death of her illegitimate child, though, Ella agrees

to marry Jim, and the first act closes with their

marriage and departure for France.

In the second act, Jim and Ella return from France, and

Ella descends into madness, as Jim attempts to pass the

bar exam. In the final scene, Ella learns that Jim has

failed to pass his bar exam again, and confesses that

she would have had to kill him had he passed. As the

scene ends, Jim pledges to be Ella’s “little boy” to her

“little girl” and both characters revert back to their

childhood games.[4]

While much of Chillun certainly deals with race,

the drama goes beyond that, showing the audience the

destruction of the couple as a result of Ella’s egotism

and Jim’s inferiority complex. As Jeffrey Ullom asserts,

“O’Neill’s racial theme is rather clumsily handled at

the beginning and then powerfully at the end.”[5]

This argument, much like most arguments concerning

Chillun, fails to look at the drama as one about the

human condition, not one merely about race. In

reexamining the context surrounding Chillun and

its first performances, though, it becomes clear how and

why much of O’Neill’s message was lost to the audience.

|

|

|

Figure 2. Press photo for the

original production of All God’s Chillun

Got Wings. The photo depicts the scene

in which Ella Downey (portrayed by Mary

Blair) kisses Jim Harris’s (portrayed by

Paul Robeson) hand. The controversy

surrounding the drama stemmed from this

interracial kiss and its implications to

1920s America.[6] |

When O’Neill first wrote Chillun, he intended for

his play to have a message beyond the dynamics of an

interracial relationship, but he perhaps made a fatal

error in including an interracial kiss. However, when

the press first learned of the interracial kiss that

O’Neill intended to perform in Chillun, the

controversy began. And, as Glenda Frank notes, “The

arguments were repeated in government offices and

churches, in living rooms and at community gatherings.

It affected the lives of hundreds of people who not only

never saw the play, but never read the script.”[7]

Beginning five months before the play’s opening

night—three months before it was originally scheduled,

in March 1924—newspapers such as the Brooklyn Daily

Eagle, the New York World, and the New

York American began running articles about

Chillun. The multitude of newspaper articles

published prior to production of the play caused much

furor and controversy for all those involved in the

production leading up to the opening night of Chillun.

While O’Neill was no stranger to controversy, the press

involved with the production of Chillun outshone

any other controversy he had thus far

experienced—including his next play, Desire Under the

Elms.[8] The

mayor of New York City, John Hylan[9],

and his compatriots attempted to stop the production of

Chillun, but were unable to, as the private

theatre company, the Provincetown Players, put on the

play. However, this did not stop the authorities from

denying a permit for children to be involved in the

production, leaving the first scene—a prologue—of

Chillun unperformed until its 1975 revival. After

Hylan’s failure to censor the play to his standards,

Hylan’s censorship took an “unconventional” turn, and

the decision to keep children from performing, as they

were “too young” was likely his last resort; it is

important to note, as Miller has observed, that “younger

children with heavier parts in uptown theatres performed

their nightly roles in freedom.”[10]

Given such constraints, the director of the 1924

production, James Light, read the first scene aloud to

the audience and the second scene continued as written.[11]

While Hylan did not get the censorship he had hoped for,

his success in preventing the first scene of the play

from being performed was a success in helping to destroy

the play that O’Neill had hoped for in writing

Chillun; much like his other race plays,[12]

the intense scrutiny and threat of censorship that

O’Neill was subject to led to the “complete distortion

of O'Neill's artistic aims, whereby his fundamentally

serious psychological studies were twisted into lewd and

obscene trash.”[13]

Chillun would fall into obscurity after its run

was finished—despite its controversial beginnings—and

time left it virtually un-performable for today’s

audiences.

Much to O’Neill’s chagrin—and despite his attempts to

prevent it—people who did not understand, or in many

cases had not even read, the play created most of the

discourse surrounding Chillun. When the first

newspaper articles were published, O’Neill brushed them

off, calling on his audience to read his script before

developing their opinion on the drama—which was

published by American Mercury[14]

months prior to its performance—instead of listening to

the sensationalist newspaper articles. However,

according to O’Neill scholar Glenda Frank, O’Neill’s

greatest downfall—that is, the biggest reason that

O’Neill and his cast became subject to backlash by the

media and the authorities—was in his casting decisions,

not in the script itself.[15]

O’Neill had decided to cast Paul Robeson—who played the

eponymous main character in The Emperor Jones—as

the ambitious, but flawed, Jim Harris and cast white

actress Mary Blair as his wife, Ella. The decision to

cast a black man opposite a white woman, in a play in

which there was an onstage kiss, made Chillun the

first play to have an interracial kiss on an American

stage. This interracial kiss, which sparked nearly all

of the media attention that the drama received, arguably

took away from O’Neill’s play overall. What did the kiss

add to the production? By the time Chillun was

finally staged, much of its themes and motifs had

already gone the way of The Hairy Ape before it,

falling into obscurity in favor of the greater

controversy. Centuries before Chillun was

written, miscegenation proved to be a volatile subject

both onstage and off. The disapproval and outlawing of

miscegenation continued beyond O’Neill as well; as

recently as 1967, miscegenation was outlawed in 16

states—laws prohibiting miscegenation were overturned by

the Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia in 1967—and,

more importantly, interracial marriage was outlawed in

30 of the 48 states at the time of the first production

of Chillun. Further, as Frank notes, “While

liaisons between black women and white men were tacitly

acknowledged, black men were mutilated and murdered for

any involvement with white women.”[16]

Perhaps if O’Neill had chosen to depict both Jim as

white and Ella as black, his drama would have been

received much differently; however, the fact remains

that O’Neill’s characters in Chillun were an

interracial couple at a time when that type of

interaction in American culture was taboo. On top of the

real life oppositions to miscegenation, though, are

theatrical productions dating as far back as

Shakespeare’s Othello in showing the downfalls of

miscegenation.[17]

The interracial kiss caused controversy among both black

and white audiences and critics. Already mentioned were

Hylan’s attempts to censor the play, hoping to stop its

production entirely, but also of note were the cries of

protest in the black community regarding Chillun.

Reverends A. Clayton Powell and J.W. Brown both shared

their negative sentiments about the production—and, it

is worth noting, both likely did not read the text of

the play, as their statements about it seemed

misinformed.[18] As

Powell said in an interview with the right-wing New

York American: “The kissing of a white woman by a

big, strapping Negro is bound to cause bad feelings. . .

. For myself and my congregation, the largest colored

Baptist Church in the city, I want to go on record as

being opposed to Mr. O’Neill’s play.”[19]

As indicated here, Powell misunderstood the nature of

the interracial kiss that would be performed, believing

that Robeson would kiss Blair and not the other way

around.[20] Much

like the other articles published by the New York

American and other newspapers, it is likely that the

greatest reason for stirring up the controversy around

Chillun was to serve a political agenda,

cementing the idea that miscegenation should be avoided

and remain illegal; as Ullom asserts:

O’Neill deserves to be

appreciated for his bravery and for not setting an

example whereby politicians and other groups could

assume that any arts organization would cave in to

pressure. In addition, the Chillun

controversy demands recognition as another futile

attempt by public figures to exploit a play for

personal gain.... Fortunately, the furor over

Chillun remains a proud moment when theater

practitioners shunned political pressure, refused to

let their play be exploited by self-serving

factions, and stood together in defense of their

art.[21]

O’Neill’s sentiments towards his drama mimic Ullom’s

assessment; in an interview with The New York Times,

O’Neill said, “Judging by the criticism it is easy to

see that the attacks are almost entirely based on

ignorance of God’s Chillun. I admit that there is

prejudice against the intermarriage of whites and

blacks, but what has that to do with my play?.... I am

never the advocate of anything in any play—except

humanity toward Humanity.”[22]

O’Neill did not hope to laud miscegenation in his play

as much as he hoped to comment on the human

condition—something that nearly all of his plays,

including those centered on race, did. Unfortunately for

O’Neill, the era that he lived in did not allow for

this, and instead, Chillun was relegated to a

play about miscegenation, due mostly to the media’s fear

mongering before the drama was ever performed. In

addition to causing undue controversy for Chillun,

the media attention surrounding O’Neill’s drama led to

death threats to O’Neill, O’Neill’s son, and Robeson.

One particular instance of a threat was made to O’Neill

on Ku Klux Klan stationary, to which, according to

Frank, O’Neill responded, “Go fuck yourself.”[23]

Aside from O’Neill and Robeson, Blair was next in danger

of the backlash surrounding the production, as a white

actress agreeing to play opposite a black man. The

New York American printed several articles

concerning this particular controversy, first declaring

that another actress, Helen MacKellar, turned down the

role upon learning that she would be playing opposite a

black man. Frank asserts that this was an incorrect

report, but gives little evidence to support this,

whereas Jeffrey Ullom suggests MacKellar was fired for

this reason—then later proposes that an octoroon replace

either Robeson or Blair.[24]

Blair was an unpredictable actress who would either soar

or sink in her performances, “but O’Neill often insisted

she be in his plays because of gratitude for her early

allegiance to the Provincetown Players.”[25]

Blair became ill with pleurisy in March 1924, causing a

delay in the production of Chillun; Blair’s

husband blamed her illness on the hate mail she

received.[26] As

much as Blair’s career seems to be buried by time and

obscurity, however, Robeson became a well-known actor

after his breakout role in Chillun, perhaps most

notably for his role in the film version of The

Emperor Jones, his subsequent film roles, and his

later civil rights activism.

Robeson did not begin his career conventionally,

however; before he became an actor, Robeson earned his

law degree at Columbia after earning his undergraduate

at Rutgers. He became disillusioned with the idea of

becoming a practicing attorney, however, and believed

that he could not be successful as a black man in the

field.[27] This

fact alone made Robeson an ideal candidate to play the

downtrodden Jim Harris, whose attempt to earn his law

degree drives Ella into madness. Robeson’s own personal

experience with the hardship faced in pursuing a law

degree—and the aftermath of actually earning one—make

Jim’s character’s struggle that much more real. Although

O’Neill’s play is written with a touch of obscurity and

expressionism, the very actor to play the main character

is the result of a failed attempt at a career in law—a

coincidence that could not have been overlooked by

O’Neill and others involved in the production of

Chillun. After discarding his goals to become a

lawyer, Robeson began to pursue acting, but did not get

his break until 1923, when he was cast in Roseanne,

put on by the African American company housed in Harlem,

the Lafayette Players.[28]

Just prior to this, O’Neill met Robeson, and in an

interview with critic Mike Gold, O’Neill said, “he had

got hold of a young man with ‘wonderful presence and

voice, full of ambition and a damn fine man personally

with real brains—not a ham....I don’t believe he’ll lose

his head if he makes a hit—as he surely will, for he’s

read the play for me.’”[29]

Because of Blair’s illness, the production of Chillun

had to be pushed back, leaving a gap in the Provincetown

Players’ productions; so, Robeson took on the role of

the title character in The Emperor Jones, which

was performed just before the opening of Chillun,

as “it seemed a good idea to fill in” the gap in

performances with The Emperor Jones, which had

been a great success in the original 1920 production.[30]

Critics, who often compared him to the original Brutus

Jones, Charles Gilpin, generally lauded Robeson’s

performance.[31]

Despite Robeson’s promising acting, Chillun did

not receive the same reputation as The Emperor Jones.

As previously mentioned, the media circus surrounding

the play created expectations and sparked outrage that

the play itself did not inspire. When Chillun was

finally performed on May 15, 1924,[32]

its reviewers were often far from fond of the play. As

one reviewer for the Brooklyn Daily News,

reported, “Possibly if [All God’s Chillun] had

not been made so notorious this welcome would have been

calmer. It is not a play to arouse great enthusiasm.”[33]

The critic ends his review with, “Affectation still

persists in the productions of the Provincetown Players,

and O’Neill is hardly free from it himself in this

instance.”[34] In a

more favorable review of Chillun, though, Ludwig

Lewisohn of the Nation states, “The production of the

Provincetown Players is notably fine, Mr. Paul Robeson

is a superb actor extraordinarily sincere and eloquent.”[35]

However, he also ends his review with a note on the

play’s mediocrity, stating, “I have seen far more beauty

and intelligence and mobility than there are in this

production and this play. I have seen nothing that so

deeply gave me an emotion comparable to what the Greeks

must have felt at the dark and dreadful actions set

forth by the older Attic dramatists.”[36]

Although Chillun was a success in terms of the

number of performances—any theatre production that has

over 100 performances is a “success”—the reviews

mentioned clearly show that Chillun was not

O’Neill’s most popular work, and did not live up to the

expectations of his previous works, such as The

Emperor Jones. As Frank notes, “Some of the critics

were so relieved that there had been no violence that

that became their news.”[37]

However, the play was most likely misunderstood by the

critics in the same way that it had been before opening

night.

Just as Reverends Powell and Brown—among many other

commentators from the black community—had misunderstood

O’Neill’s play prior to its performance, white critics

had the same difficulties in their reviews of the play.

Despite O’Neill’s efforts, the most memorable and

notable part of his drama was the interracial marriage

and kiss, and not his observations on the human

condition. As O’Neill said in an interview with The

New York Times, which was published days before

opening night, “The persons who have attacked my play

have given the impression that I make Jim Harris a

symbolical representative of his race and Ella of the

white race—that by uniting them I urge intermarriage.

Now Jim and Ella are special cases and represent no one

but themselves.”[38]

Unfortunately, this claim fell largely on deaf ears.

After stating that the play was boring, reviewer Arthur

Pollock of the Brooklyn Daily News incorrectly

labeled the play as “seven scenes depicting...stages in

the progress of the miscegenetic romance.... It is a

sharp and pertinent analysis of the question of

intermarriage between whites and blacks...”[39]

It seems as though Pollock had not read O’Neill’s New

York Times interview at all in making these claims

about Chillun; his analysis of the play is

clearly propped up by the media spectacle that was

created around the drama, and the apparent views on race

and miscegenation that had existed in the United States

at the time of the play’s production. The failure of the

critics of Chillun was not only because of the

media attention the play received in the months leading

up to its opening night but also in their inability to

see beyond the racial aspects of the play. Many reviews

of Chillun fail to go beyond an analysis of

O’Neill’s portrayal of race and intermarriage, to the

autobiographical elements and more that are beneath the

surface. It is no coincidence that O’Neill named the

main characters after his parents—Ella was his mother’s

name, and James his father’s. The struggles that the

couple in Chillun face is not exclusive to an

interracial couple, but rather to a couple who does not

see themselves on equal footing. Ella is intent upon

feeling superior to Jim because of the color of her

skin, but this could easily be changed to suit any

number of other conditions. Fortunately, one reviewer,

Lewisohn, did see the merit of the play beyond the

intermarriage; in his review he asserts, “But the

problem he has selected cleaves so near the bone of

human life itself that it possesses a transcendent

symbolic character.”[40]

This reviewer is one of a few who took this stance and

who saw beyond the black Jim and white Ella into an

examination by O’Neill of human life on the whole.

O’Neill asserts in his New York Times interview,

“To me every human being is a special case, with his or

her own special set of values.... But it is the manner

in which those values have acted on the individual and

his reactions to them which makes of him a special

case.”[41] Jim

Harris and Ella Downey were O’Neill’s special cases in

Chillun, and their race was merely a peripheral

catalyst to their destruction.

Chillun has been revived just three times since

1924: in 1975, in 2001, and in 2013. This fact is not

surprising, as the drama is inevitably racist to today’s

eyes, but in spite of the fact Chillun is rarely

staged, the most recent performance of the drama was in

September 2013. This performance is of note not because

of the performance itself, but because of the director’s

decision to segregate the audience. Performed at the

Jack Theatre in Brooklyn, the audience members were told

to sit in either the “black” or “white” sections—which

faced each other—and those who did not fall into either

category were forced to choose between the two.[42]

This production of the play seems to be more of a study

of its impact—or perhaps its continued relevance—than

anything else, highlighting the audience more than the

performers, perhaps to help illuminate the division

between the experience of these two groups even in

today’s society. While this production did not have the

same stigma and controversy attached to it as the

original, it marks an important point in the play’s

history, which can only be understood through the study

of its original performance.

Although O’Neill found that Chillun was largely

misunderstood, as the drama was much more than a play

about miscegenation, the fact remains that this was his

last race play. Despite his efforts to downplay the

interracial marriage and kiss in the drama, O’Neill’s

play is not only about the human condition—as he had

intended it to be—but also one about the black condition

in the United States in the 1920s. Much like The

Emperor Jones and The Hairy Ape, however,

O’Neill failed to completely grasp this particular human

condition completely, leaving Chillun largely

misunderstood and the subject of great controversy. As

the 2013 production demonstrated, the racial tension

that O’Neill felt in his lifetime has not completely

disappeared. Chillun remains a relevant piece of

writing today, from the controversy that began its fame

to the racial and human strides O’Neill attempted to

make in the play, despite their shortcomings.

NOTES

[1]Playbill, “All

God’s Chillun Got Wings,” eOneill.com,

http://www.eoneill.com/artifacts/AGC1.htm.

[2]Eugene O’Neill,

All God’s Chillun Got Wings in O’Neill

Complete Plays, 1920-1931 (New York: Library of

America, 1988), 282.

[3]O’Neill, All

God’s Chillun, 287.

[4]Ibid., 315.

[5]Jeffrey Ullom,

“Fear Mongering, Media Intimidation, and Political

Machinations: Tracing the Agendas Behind the All

God’s Chillun Got Wings Controversy,” Comparative

Drama 45:2 (2011): 82.

[6]Helen Deutsch

and Stella Hanau, “Scene in O'Neill's All God's Chillun

Got Wings in which Paul Robeson kissed Mary Blair's hand

and created a national uproar,” Provincetown Playhouse,

Wikimedia Commons,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:All_God%27s_Chillun_Got_Wings.png.

[7]Glenda Frank,

“Tempest in Black and White: The 1924 Premiere of Eugene

O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings,”

Resources for American Literary Study 26:1 (2000):

75.

[8]Desire Under

the Elms, which was first produced 1924, included

infanticide and adultery among other taboo themes,

leading to the arrest of the entire cast in California.

[9]According to

Jordan Miller, in his book, Eugene O’Neill and the

American Critic, Hylan “took a personal interest” in

the play, and Hylan “intervened in an attempt to prevent

the staging of a play that would dare to show a white

woman kissing a Negro's hand” which he considered a

“problem play” that had no depth beyond the

controversial concept of miscegenation (59).

[10]Jordan Y.

Miller, Eugene O’Neill and the American Critic

(London: Hamdon Archon Books, 1962), 59.

[11]Arthur Pollock,

“All God’s Chillun,” Brooklyn Daily News, May 16,

1924.

[12]The Hairy

Ape, for instance, ran for two months at the

Provincetown Playhouse before it was charged with being

“obscene, indecent, and impure,” according to a New

York Times article published in May 1922. Although

nothing ever came of attempt at censorship, O’Neill’s

play was no longer what O’Neill had intended it to be,

but rather the work of a perverse playwright (Miller,

58). Much like All God’s Chillun Got Wings would

become a play about miscegenation, The Hairy Ape’s

troubles with the press and the authorities left it

stripped of the artist’s intent.

[13]Miller,

Eugene O’Neill and the American Critic, 58.

[14]Eugene O’Neill,

All God’s Chillun Got Wings in American

Mercury, Volume I, Number 2 (New York: Alfred A.

Knopf, 1924).

[15]Frank, “Tempest

in Black and White,” 82.

[16]Frank, 77.

[17]Ibid., 77.

[18]Ibid., 82.

[19]Powell qtd. in

Frank, “The Tempest in Black and White,” 82.

[20]Appearing at

the end of the play, O’Neill’s stage directions read: “(She

kisses his hand as a child might, tenderly and

gratefully.)” O’Neill, All God’s Chillun,

315.

[21]Ullom, “Fear

Mongering,” 94-95.

[22]Louis Kantor,

“O’Neill Defends his Play of Negro: Dramatist Asserts He

Does Not Advocate Union of Black and White Races in ‘All

God’s Chillun Got Wings,’” The New York Times,

May 11, 1924.

[23]Frank, “Tempest

in Black and White,” 79.

[24]Ibid., 86.

[25]Yvonne Shafer,

Performing O’Neill (New York, St. Martin’s Press,

2000), 15.

[26]Frank, “Tempest

in Black and White,” 86.

[27]Shafer,

Performing O’Neill, 13.

[28]Ibid., 14. The

Lafayette Players were the first black theatre company

in the United States, as well as the first theatre

company to desegregate their audience around 1912. The

Provincetown Playhouse followed suit in this regard, as

its theatre was also desegregated.

[29]O’Neill qtd. in

Shafer, Performing O’Neill, 14.

[30]Shafer,

Performing O’Neill, 15.

[31]Gilpin became

popular for his portrayal of Emperor Jones, but because

of his refusal to use the word “nigger” during his

performances, as well as his reputation as an alcoholic,

O’Neill severed ties with him. Despite his original

promise, Gilpin’s reputation fell into obscurity, and he

eventually had a breakdown at the age of 50—before his

death at 51. O’Neill said of Gilpin: “As I look back on

all my work I can honestly say there was only one actor

who carried out every notion of a character I had in

mind. That actor was Charles Gilpin as the Pullman

porter in The Emperor Jones.” (Shafer, Performing

O’Neill, 13).

[32]The performance

had a month-long run at Provincetown Playhouse, then

transferred to the Greenwich Village Theatre for 100

performances, according to Ullom’s article (83).

[33]Pollock, “All

God’s Chillun.”

[34]Pollock, “All

God’s Chillun.”

[35]Ludwig Lewisohn,

“All God’s Chillun,” The Nation, June 4, 1924.

[36]Lewisohn, “All

God’s Chillun.”

[37]Frank, “Tempest

in Black and White,” 87.

[38]Kantor,

“O’Neill Defends His Play of Negro.”

[39]Pollock, “All

God’s Chillun.”

[40]Lewisohn, “All

God’s Chillun.”

[41]Kantor,

“O’Neill Defends His Play of Negro.”

[42]Claudia la

Rocco, “Divided Society and a Divided Audience,” The

New York Times, September 10, 2013, C4.

WORKS CITED

Als, Hilton. “Master of Disguise: Paul Robeson and

The Emperor Jones.” The Criterion Collection.

2013.

http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/1269-master-of-disguise-paul-robeson-and-the-emperor-jones.

Bogard, Travis. Contour in Time. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1988.

Bower, Martha Gilman. “All God’s Chillun:

Religion and ‘Painty Faces’ versus the NAACP and the

Provincetown Players.” Laconics 1 (2006).

Frank, Glenda. “Tempest in Black and White: The 1924

Premiere of Eugene O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got

Wings.” Resources for American Literary Study

26:1 (2000): 75-89.

Gagnon, Donald P. “Pipe Dreams and Primitivism: Eugene

O’Neill and the Rhetoric of Ethnicity.” PhD diss.,

University of South Florida, 2003.

Hinden, Michael. “The Transitional Nature of All

God’s Chillun Got Wings.” The Eugene O’Neill

Newsletter 4 (1980).

http://www.eoneill.com/library/newsletter/iv_1-2/iv-1-2b.htm.

Kantor, Louis. “O’Neill Defends his Play of Negro:

Dramatist Asserts He Does Not Advocate Union of Black

and White Races in ‘All God’s Chillun Got Wings.’”

The New York Times, May 11, 1924.

Lewisohn, Ludwig. “All God’s Chillun.” The Nation,

June 4, 1924.

http://www.eoneill.com/artifacts/reviews/agc1_nation.htm.

McKnight, Harry W. “The Black O’Neill: African American

Portraiture in Thirst, The Dreamy Kid,

Moon of the Caribees, The Emperor Jones,

The Hairy Ape, All God’s Chillun Got Wings,

and The Iceman Cometh.” M.A. thesis, Ohio

Dominion University, 2012.

Miller, Jordan Y. Eugene O’Neill and the American

Critic. London: Hamden Archon Books, 1962.

Morrison, Michael A. “Emperors Before Gilpin: Opal

Cooper and Paul Robeson.” Eugene O’Neill Review

33:2 (2012): 159-173.

Pollock, Arthur. “All God’s Chillun.” Brooklyn Daily

News, May 16, 1924.

La Rocco, Claudia. “Divided Society and a Divided

Audience: ‘All God’s Chillun Got Wings,’ Revived in

Brooklyn.” The New York Times, September 10,

2013.

Shafer, Yvonne. Performing O’Neill. New York: St.

Martin’s Press, 2000.

Ullom, Jeffrey. “Fear Mongering, Media Intimidation, and

Political Machinations:

Tracing the Agendas Behind All God’s Chillun Got

Wings Controversy.” Comparative Drama 45:2

(2011): 81-97.